By Alex McPherson

Playful and excoriating in equal measure, director Igor Bezinović’s documentary “Fiume o Morte!” (Fiume or Death!) examines the absurdity, horror, and sobering legacy of fascism, presenting an irreverent reframing of place and history that gives power back to the people.

Bezinović’s film takes place in his hometown of Rijeka, Croatia, a port on the Adriatic about 50 miles from Italy, with a tumultuous history. The city, once known as Fiume, was ruled by the Hapsburgs during World War I. After the War ended, it was left under the control of Yugoslavia, not Italy. This surprised many, including the vainglorious Italian aristocrat, poet, drug addict, womanizer, and army officer Gabriele D’Annunzio (a friend and inspiration for the young Benito Mussolini).

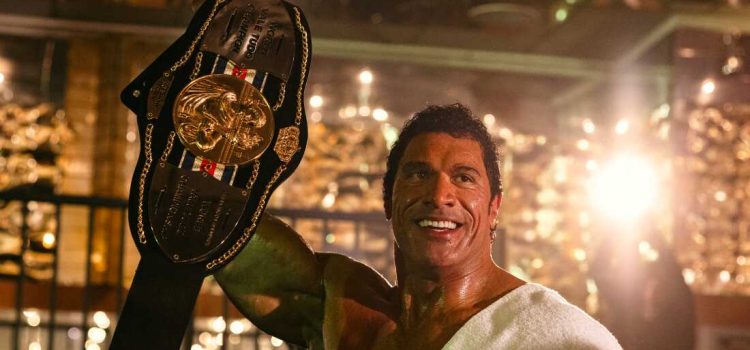

In 1919, fueled by vanity and nationalism, D’Annunzio led an insurgency with 186 unemployed and hate-filled “legionaries” to occupy the city and claim it as an independent, pro-Italy city-state with himself as its supreme ruler. D’Annunzio’s leadership didn’t last long; he was forced out of power by none other than Italy itself in 1920.

Bezinović aims to reckon with D’Annunzio’s complicated legacy on both sides of the Italo-Croatian border with “Fiume o Morte!” He also, just as importantly, cuts the failed despot down to size.

Walking through a vibrant farmer’s market in present-day Rijeka, Bezinović asks passers-by whether they know who the man was — some have no idea, others are quick to label D’Annunzio a fascist, and others aren’t willing to make such sweeping statements, noting that he was also a “great poet and lover.”

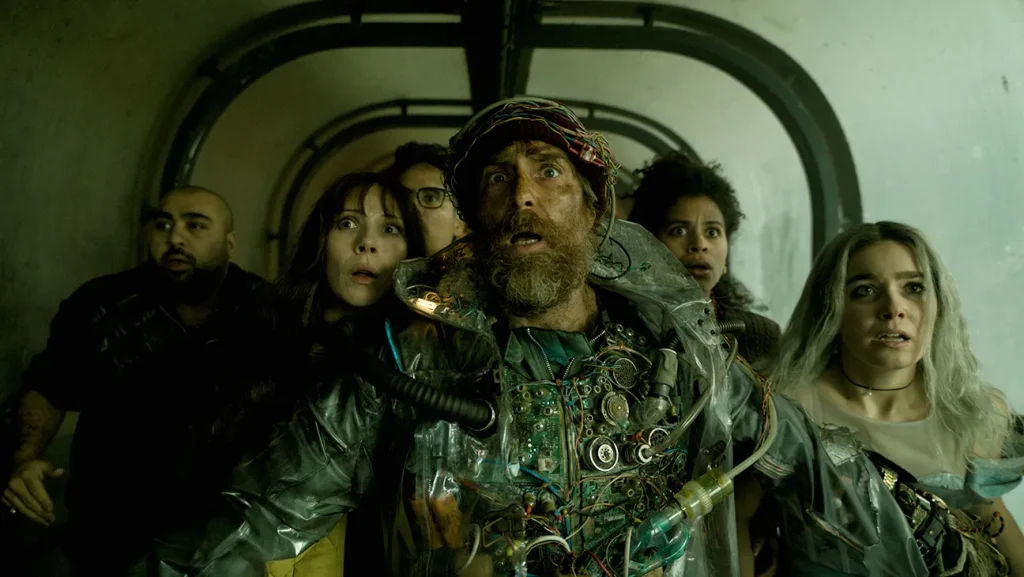

Bezinović reveals that he’s making a film about D’Annunzio’s coup, and he hires non-actor residents of Rijeka (including plumbers, musicians, and professors, some recruited directly from that farmers market, and at least one pet dog) to play every role and provide the film’s dry-humored narration, with several bald men recruited to play the (in)famously hairless D’Annunzio.

The historical reenactments themselves (which take up the bulk of “Fiume o Morte!”) treat D’Annunzio with the respect he deserves – that is, none at all. Performed with period-accurate costumes, keen attention to framing (Gregor Božič’s cinematography is beautiful), and a limited budget encouraging bucketloads of mocking comedy, Bezinović replicates scenes and tableaus from thousands of photographs and video footage documenting D’Annunzio’s “heroic” coup with a winking, anachronistic twist.

“Fiume o Morte!” jumps back-and-forth between these “grandiose” historical documents and a considerably less impressive present. The goofy yet faithful reenactments (in the same locations) seem out of place within the colorful hustle and bustle of modern-day Rijeka.

A photo of D’Annunzio speechifying before hundreds of onlookers turns into an aged non-actor revealed (via a slow zoom-out) to be speaking to an audience of two family members. A high-stakes meeting between generals concludes with D’Annunzio walking uphill to play rock music with his band as trucks leisurely drive by on their way to storm the city.

Some photos and videos — like a sword-wielding D’Annunzio posing naked draped with the Fiume flag, or homoerotic revelry on the beach with his unemployed legionaries — barely need exaggeration at all in the present-day. Sometimes onlookers stop to take pictures, others essentially ask “What the Hell are you doing?”

The reenactments are absurd and satisfyingly savage, emphasizing the ridiculousness of D’Annunzio’s occupation and putting his story in the hands of the community he attempted to suppress; a violent past juxtaposed by a resilient present that has endured and, as Bezinović keenly points out, is still grappling with D’Annunzio’s legacy and broader society’s continued cozying up to his fascist ideals.

Indeed, although “Fiume o Morte!” is often a breezy, immensely enjoyable viewing experience (particularly charming when narration highlights the backgrounds of each featured member of the ensemble), Bezinović never loses sight of the barbarity of D’Annunzio’s self-imposed mission, and the consequences of his violently prejudiced enterprise that helped pave the way for Kristallnacht.

Bezinović is selective about what he chooses to recreate, in certain moments relying entirely on historical artifacts instead of reenactments to drive home the oppressiveness of D’Annunzio’s rule and the tragic consequences for the (especially non-Italian) citizenry, as well as painting clear parallels between then and now.

Not only do we get a clear picture of D’Annunzio’s hubris and failures, but also a spirited portrait of Rijeka and its diversity, and caustic reminders of how his memory lives (and, in terms of younger generations, dies) among the populace. Just nearby in the Italian city of Trieste, for example, statues are continuing to be erected of the bald buffoon to this day, more celebratory than critical.

“Fiume o Morte!,” then, works as an irreverent history lesson, a reclamation of storytelling by the community he claimed he conquered, and an example of how nationalism and pride distort the truth. And that art, liberating in its creative freedom, has the ability to both entertain and educate, empowering those whose stories were brushed over by forces of evil.

This is a masterful documentary that’s enlightening and downright ingenious – an absolute must-watch that stands tall among the year’s best films thus far.

“Fiume o Morte!” Is a 2025 documentary directed by Igor Bezinovic. It was the official submission of Croatia for the ‘Best International Feature Film’ category of the 98th Academy Awards in 2026. It is 1 hour and 52 minutes run time. It can be seen at the Webster Film Series on March 8. Alex’s Grade: A+

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.