By Lynn Venhaus

Sins of the past collide with a volatile present in the intense gut-punch that is August Wilson’s “King Hedley II,” part of his American Century Cycle now in return rotation at The Black Rep.

One of the foremost interpreters of Wilson’s work, director Ron Himes superbly creates a powder keg of family secrets, desires for fresh starts, and hopes punctured by despair.

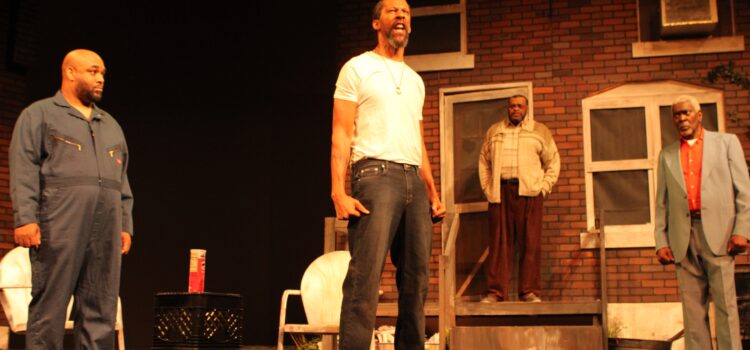

Shaping vivid portrayals, an outstanding ensemble conveys an abundance of passion in a heartbreaking and tragic tale.

The ninth of Wilson’s 10 plays set in the 20th Century, “King Hedley II,” written in 1999, takes place in Reagan’s America 1985, when class struggles were escalating.

This was a fraught time for black men and women trapped by circumstances – few opportunities and an alarming rise in gun violence, teen pregnancies and unemployment. Wilson hammers all those points home in poetic dialogue that spills out in blistering, breathtaking monologues that offer perspective.

Himes understands the rhythms of these individual characters so that their story arcs are distinctive – and the six intertwining connections are convincing. It is masterful, moving work from Ka’ramuu Kush as rage-filled King and Alex Jay as his conflicted wife Tonya, local legends Denise Thimes as matriarch Ruby and J. Samuel Davis as ramblin’, gamblin’ Elmore, with strong support from A.C. Smith as evangelical neighbor Stool Pigeon and Geovonday Jones as King’s pal Mister.

With daily indignities chipping away at his self-respect, King is attempting to overcome a world of hurt to rebuild his life. He just spent seven years in prison for killing a man who disfigured his face. Now, he wants to provide for his family as he hustles stolen refrigerators and dreams of opening a video store with his best friend Mister.

Trouble seems to lurk everywhere, to pull him back, and his life could blow up at any moment because of all these small fires and volatile situations fanning the flames.

Such is the action in a backyard of Pittsburgh’s Hill District, fertile ground for Wilson’s dark, complex story about the widening gulf between the haves and have-nots. Some of the characters we met in his “Seven Guitars” reappear a generation later.

“Seven Guitars,” presented in 1995, confronted obstacles faced by a blues musician, Floyd “Schoolboy” Barton, who lived in a boarding house in 1948. In that one, Ruby, visiting from Alabama, is pregnant with the son she names King Hedley II. Hedley is a prominent character, although the father’s paternity is not explained. Stool Pigeon appears as musician Canewell, one of Floyd’s best buds who is now collecting newspapers and trying to maintain historical records in “King Hedley II.” His friend, Red Carter, is Mister’s father.

Wilson’s 10 plays, each exploring the African American experience by decade over the course of 100 years, have been performed by the Black Rep before. During this second go-round for the anthology, I have seen them all since “The Piano Lesson” in 2013, with “Jitney” in 2022 and “Two Trains Running” in 2020 earning outstanding production awards from the St. Louis Theater Circle.

Next season, they will complete this recent cycle with “Radio Golf,” which takes place in the 1990s and was Wilson’s final work, presented in 2005.

All powerful in their own ways, these finely acted and impeccably produced shows illuminate black heritage and specific challenges.

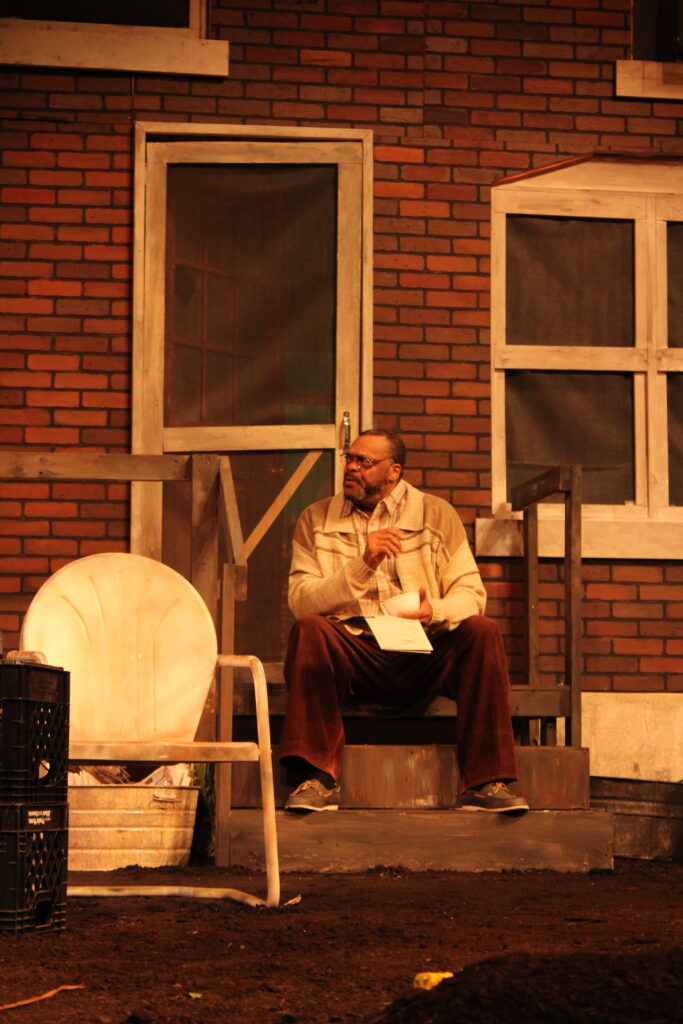

This production’s gritty look immerses us into the neighboring row houses’ struggles through scenic designer Timothy Jones’s shabby stoop of Stool Pigeon’s and the grimy back porch of Miss Ruby’s delapidating family home while Travis Richardson’s lighting design, Alan Phillips’ sound design and Mikhail Lynn’s props create an authentic daily atmosphere.

Kush’s King gains our sympathies as he expresses his self-doubts and displays his vulnerabilities, detailing the reasons behind his noticeable facial scar, prison sentence, and his impoverished life to date.

He’s trying to grow flowers in a neighborhood of few success stories, an apt metaphor, but an unwavering sense of community is present, even as they lament the disrespectful thug environment encroaching on their turf they try so hard to protect.

The cast excels in fleshing out their characters’ colorful personalities and backstories so that you understand their motivations and philosophies on life. Stool Pigeon and Mister present some welcome humor, which both Smith and Jones are skilled at providing.

Stool Pigeon’s frequent quoting of the Bible often gives the play a spiritual angle that reveals more as it unfolds. “God got a plan. That medicine can’t go against God. God do what he want to do. He don’t have to ask nobody nothing,” Smith matter-of-factly states.

Wilson’s views on disadvantaged lives hit hard as their truths tumble out – exemplified by a fiery outburst from Tonya on why she doesn’t want another child, and we feel all of Jay’s anguish.

Davis, a two-time St. Louis Theater Circle acting award winner, is silky-smooth as the charming Elmore, a rascal and former suitor that reconnects with Ruby. He’s trying to soothe his soul on some of the messes of his life.

Davis’s stellar track record with Wilson’s plays continues in one of his finest portrayals, deftly maneuvering the rapid-fire exchanges of a flashy con artist always trying to score.

Thimes, known as one of the best jazz singers in town, fully embodies Ruby, trying to find peace in her golden years, and looking back at regretful missteps.

Costume designer Kristie Chiyere Osi has outfitted the working-class characters specifically, with Elmore’s slick suits and snazzy hats an interesting contrast to everyone else’s casual attire.

The cast is riveting as the action heats up, leading to an explosive climax that left me shaken. The tension is telegraphed all through Wilson’s exceptional prose, as past violence is recounted, but it still stuns.

Nominated for both the Pulitzer Prize and the 2001 Tony Award for Best Play, “King Hedley II” is impactful in its goal, to better understand behavior when people are robbed of dignity and humanity. That message resonates with The Black Rep’s insightful staging.

The Black Rep presents “King Hedley II” from June 19 to July 14 at the Edison Theatre on the Washington University campus. An intergenerational matinee is June 26. It is 2 hours, 45 minutes, with an intermission, and contains mature language. For more information, www.theblackrep.org.

Lynn (Zipfel) Venhaus has had a continuous byline in St. Louis metro region publications since 1978. She writes features and news for Belleville News-Democrat and contributes to St. Louis magazine and other publications.

She is a Rotten Tomatoes-approved film critic, currently reviews films for Webster-Kirkwood Times and KTRS Radio, covers entertainment for PopLifeSTL.com and co-hosts podcast PopLifeSTL.com…Presents.

She is a member of Critics Choice Association, where she serves on the women’s and marketing committees; Alliance of Women Film Journalists; and on the board of the St. Louis Film Critics Association. She is a founding and board member of the St. Louis Theater Circle.

She is retired from teaching journalism/media as an adjunct college instructor.