By Lynn Venhaus

A trio of ragtag revolutionaries cling to their cause and their rules as they hide from an authoritarian regime in the very quirky and vague-on-purpose “Pictures from a Revolution” (Quadri di una rivoluzione) by Sicilian playwright Tino Caspanello.

Strange but intriguing because of the agile skills of the acting quartet, this U.S. premiere is uneven in tone, perhaps because of the English translation by Haun Saussy, but then again, Caspanello is committed to keeping us guessing and in the esoteric structure with the sketchiest details.

While the men – called by numbers, initially act like the Three Stooges, they are in a serious battle to maintain their resistance against totalitarian forces in an unidentified country.

While living inside the walls of a stadium, they take turns being on guard, convinced enemies are lurking outside, waiting to capture the rebels. They make grand gestures and believe there is a purpose to their righteous anger. After all, they are following their rules.

What do they stand for, and why are they still fighting? They’re hungry, tired and cranky, debating actions to take. J. Samuel Davis, in a wonderfully comic role, is the sage 584, the oldest of the group. He decides to journey outside their encampment in hopes of lassoing a cow – for milk and eventually meat. His slapstick is a delight.

Instead, he has captured an unnamed woman (Lizi Watt), who ferociously fights him like a caged animal on the attack. They are confused by her then eventually won over by her charms. She changes her story but begs them to believe her. She must stay or they may be found out.

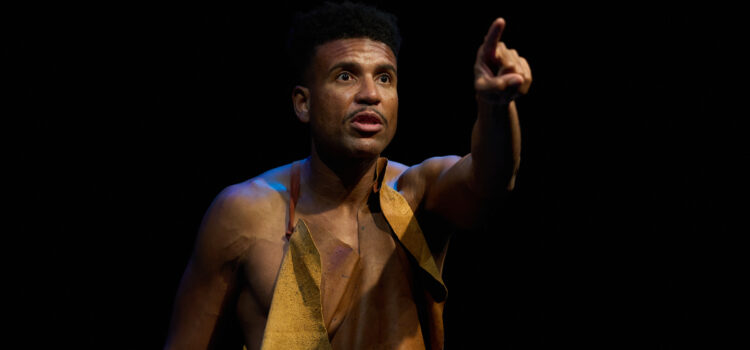

Watts is impressive in this fierce and fearless role that she tackles with robust physicality. Should they trust her or is she dangerous? She throws off the dynamic of the trio – Isaiah DeLorenzo is at his idiosyncratic best as 892, the chief. He likes to pontificate about ideals and how important their mission is. We don’t really know who the enemy is.

As the youngest rebel 137, Andre Eslamian has another fine turn after strong work in Lize Lewy’s “Longing” last summer and in SATE’s “The Palpable Gross Play: A Midsummer adaptation” the year before. His character seems the most pragmatic and tends to a garden.

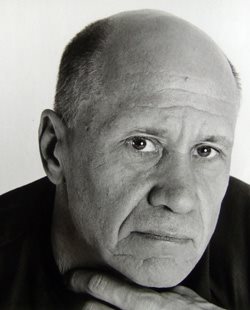

Director Philip Boehm has added a performance art quality to the production by his artful staging, and using dance-like movements for all characters, which become more pronounced as the 90-minute play unfolds. Cecil Slaughter was the movement coordinator, and the ensemble is elegantly in sync.

Another unusual aspect of this play is its inclusion of 11 works of art by some of the world’s most famous painters – shown as slides, with Boehm narrating as if he’s teaching an art history class. Among them: “The Night Watch” by Rembrandt, “Leda Atomica” by Salvador Dali, “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” by Marcel Duchamp, “Ballet Rehearsal on Stage” by Edgar Degas and “Cornfield with Crows” by Vincent Van Gogh.

The scenes often echo the themes of the famous painting being shown before it, which is interesting. Patrick Huber’s projection work is fluid in presenting the paintings. He also worked on the scenic design, fashioning an enclave for the squatters that has a lived-in feel, aided by propmaster Rachel Seabaugh.

Because the dialogue is fanciful, and the situation almost surreal like, there is little emotional connection, and the conflicts are both petty and daunting. Much bickering wears down one’s goodwill — but the funny situations do elicit laughs.

The technical work is uniformly first-rate, with Michele Friedman Siler’s costume design giving each man a distinctive look and outfitting The Woman in a slinky dress, an evening bag and nice heels, so that questions are raised by her appearance.

Boehm and Huber also handled the intricate sound design while Steve Carmichael took care of the lighting design, reflecting the different times of day. Joe Schoen worked as a vocal consultant.

“Pictures from a Revolution” continues Upstream Theater’s commitment to exploring thought-provoking works from around the globe that are universal in its themes. At times, it seems like theater of the absurd, while other moments are dark comedy.

And the cast’s commitment to bringing different elements of humanity to their roles is admirable, which is why their performances stand out, not only individually, but as a quartet.

Upstream Theater presents “Pictures from a Revolution” from Jan. 24-26, Jan. 30-31, Feb. 1-2, and 6-8, at The Marcelle Theater, 3310 Samuel Shepard Drive, St. Louis. There is a 2 p.m. matinee and an 8 p.m. performance on Saturday, Feb. 8. The play runs for 1 hour, 30 minutes without intermission. This play contains language that some may find offensive and well as discussion of mature themes. For tickets, contact metrotix.com. For more information, visit www.upstreamtheater.org.

Lynn (Zipfel) Venhaus has had a continuous byline in St. Louis metro region publications since 1978. She writes features and news for Belleville News-Democrat and contributes to St. Louis magazine and other publications.

She is a Rotten Tomatoes-approved film critic, currently reviews films for Webster-Kirkwood Times and KTRS Radio, covers entertainment for PopLifeSTL.com and co-hosts podcast PopLifeSTL.com…Presents.

She is a member of Critics Choice Association, where she serves on the women’s and marketing committees; Alliance of Women Film Journalists; and on the board of the St. Louis Film Critics Association. She is a founding and board member of the St. Louis Theater Circle.

She is retired from teaching journalism/media as an adjunct college instructor.