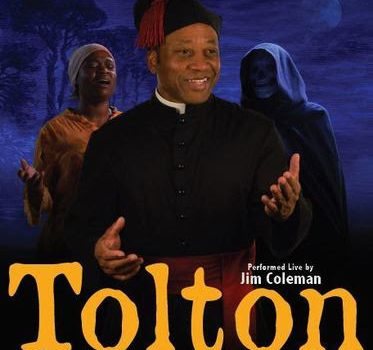

Jim Coleman stars in “Tolton: ‘From Slave to Priest’

A professional theatrical one-man-show and multi-media presentation of the fascinating life of Father Augustus Tolton (1854-1897),the first African-American priest in the U.S. Catholic Church, will take place on Friday, Feb. 1, at 7 p.m. at St. Peter’s Cathedral in Belleville, Ill.The performance is free and open to the public.Once a slave, he was ordained a Catholic priest and ministered in southern Illinois and Chicago.The Vatican office for saintly canonizations is currently studying Father Tolton’s life.For more information, visit the website about the professional production, https://www.stlukeproductions.com/dramas/toltonor contact the diocesan Rector, Msgr. John Myler, pastor of the Cathedral, at 618-234-1166.

Below is Bishop Edward K. Braxton’s reflection on Father Tolton’s life:Fr. Augustus Tolton (1854-1897) lived his brief life of forty-three years during a particularly troubled period in American history – the period of the “middle passage” when cargo ships from Europe made their way to west Africa and enslaved 1000’s of human beings, transporting them across the Atlantic in chains and stacked on top of one another, “selling” them to plantation owners. The ships returned to Europe filled with tobacco and cotton cultivated by slave labor. Augustus was born a slave of slave parents who were all baptized Catholics by arrangement of the Catholic families who “owned” them. His father, Peter Tolton, left to fight for freedom with Union Troops at the start of the Civil War. Much later it was discovered that he died in a hospital in St. Louis. His wife, Martha Jane Tolton, having accomplished a harrowing escape from those who “owned” her and her children, found refuge in Quincy, Illinois, a station of the Underground Railroad that assisted escaping slaves to reach freedom. There in Quincy, she raised her children, seeking out Catholic schools for them. Augustus’s boyhood and youth had as backdrop the period of Reconstruction and the nation’s ambivalence about the plight of freed People of Color.As a young boy, Augustus worked long hours in a tobacco factory. Several local priests and sisters took Tolton under their wing to tutor him in the catechism, languages, including Latin, and the necessary academic subjects that won him entry into Quincy College, which was conducted by the Franciscan Fathers.He was mature for his age and he showed signs of a vocation to the priesthood. But, it proved difficult finding a seminary in the United States that would take a black student. After years of searching and petitioning only to receive letters of denial or no response at all, the Franciscan Fathers were able to prevail upon their Superior General in Rome – Augustus Tolton was accepted and entered the college of the Propagation of the Faith and studied philosophy and theology for six years with seminarians from mission countries. He was ordained to the priesthood on April 24, 1886 at the Basilica of St. John Lateran, the Cathedral Church of the Pope, the Bishop of Rome.The PriesthoodFearing that Fr. Tolton’s priesthood would be filled with suffering given the prevailing racial prejudice that prevailed in the United States, his superiors thought he would serve as a missionary priest in Africa. However, his mentor, Giovanni Cardinal Simeoni, challenged the Church in the United States to accept Fr. Tolton as its first African-American priest. “America has been called the most enlightened nation in the world. We shall see if it deserves that honor.” He returned to his home Diocese of Alton, Illinois, which once embraced the Dioceses of Springfield and Belleville. After his First Mass in Quincy, he was assigned to St. Joseph Church, the “Negro Parish.” Many local priests counseled their parishioners to stay away from St. Joseph Church. When White parishioners went to Fr. Tolton’s parish to receive sacraments and counsel from him, a neighboring Catholic Pastor and Dean of the area ordered him, in no uncertain terms, to restrict himself to serving the People of Color. He also complained several times to the local Bishop, demanding that White parishioners be ordered to stay away from Fr. Tolton’s parish. Many White People stopped attending the church while others remained steadfast in their support of Fr. Tolton and the Negro apostolate. In midst of this ferment, Fr. Tolton suffered under increasing isolation and feelings of apprehension, perpetrated by local clergy with whom he needed association, to say nothing of the town’s lay Catholics. He became well known around the country as the first visible Black Catholic priest, renowned for his preaching and public speaking abilities and his sensitive ministry to everyone. He was often asked to speak at conventions and other gatherings of Catholics of both races. At that time, a fledgling African-American Catholic community needed organization in Chicago. Archbishop Patrick Feehan, aware of Fr. Tolton’s painful experiences in the Alton Diocese, received him in Chicago in 1889. His Bishop did not hesitate to give permission for the transfer, accusing the priest of creating an unacceptable situation by inviting fraternization between the races. Fr. Tolton opened a storefront church in Chicago and later built a church for the growing African-American Catholic community on the South Side at 36th & Dearborn, managing to complete the lower level where the community worshipped for some time while he raised funds for the church’s completion. Katherine Drexel (now Saint Katherine), foundress of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament (for African-American women excluded from other orders), contributed to the building of the church.Fr. Tolton became renowned for attending to the needs of his people with tireless zeal and a holy joy. He was a familiar figure in the littered streets and dingy alleys, in the Negro shacks and tenement houses. Father Tolton had the pastoral sensitivity needed to bring hope and comfort to the sick and the dying, to bestow spiritual and material assistance, and to mitigate the suffering and sorrow of an oppressed people.His biographers write that Fr. Tolton worked himself to exhaustion while dealing with the internalized stress that came with navigating the rough, cold waters of racial rejection. Like most poor People of Color, Fr. Tolton lacked adequate health care. The first week of July 1897, an unusual heat wave hit Chicago, during which a number of people died. Father Tolton suffered a heat-stroke under the daily scourge of 105 degree heat and collapsed on the street. Doctors at Mercy Hospital worked frantically for four hours to save his life. But like St. Paul, Augustus had run the race, kept the faith, and fought the fight. He died 8.30 in the evening of July 9th with his mother, his sister, a priest, and several nuns at his bedside. Funeral Masses were celebrated for him in Chicago and in Quincy, where he wanted to be buried. Large crowds of priests and laity participated, singing his favorite hymn, Te Deum (“Holy God We Praise Thy Name”).ReplyForward

Lynn (Zipfel) Venhaus has had a continuous byline in St. Louis metro region publications since 1978. She writes features and news for Belleville News-Democrat and contributes to St. Louis magazine and other publications.

She is a Rotten Tomatoes-approved film critic, currently reviews films for Webster-Kirkwood Times and KTRS Radio, covers entertainment for PopLifeSTL.com and co-hosts podcast PopLifeSTL.com…Presents.

She is a member of Critics Choice Association, where she serves on the women’s and marketing committees; Alliance of Women Film Journalists; and on the board of the St. Louis Film Critics Association. She is a founding and board member of the St. Louis Theater Circle.

She is retired from teaching journalism/media as an adjunct college instructor.