By Alex McPherson

Depicting a frightening near-future scenario, Alex Garland’s “Civil War” is a sincere ode to journalists, a chilling warning to take history seriously, and a stark reminder to never lose our humanity amid chaos.

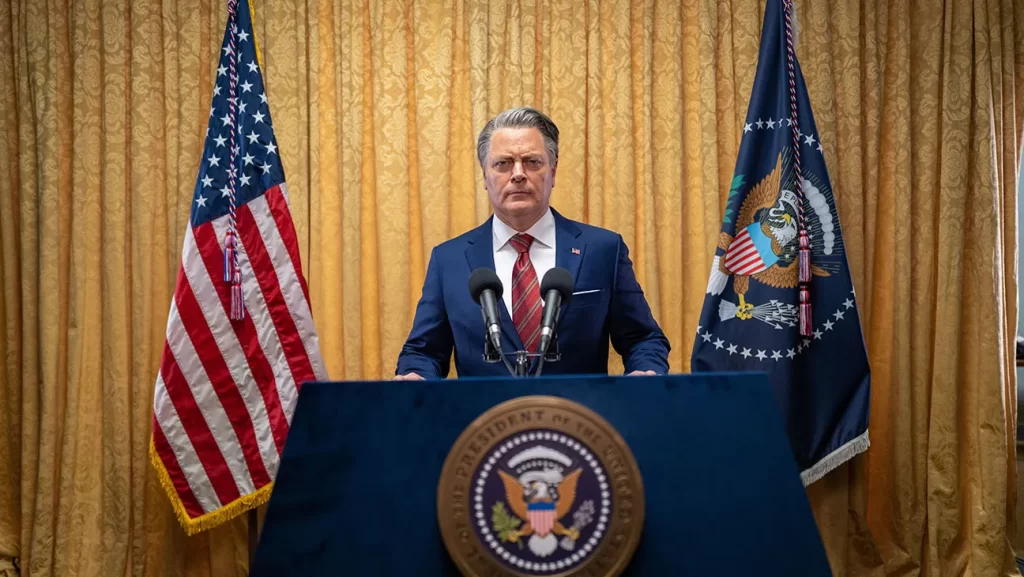

Eschewing backstory to throw us right into the middle of the conflict, “Civil War” depicts an America where an authoritarian, three-term president (Nick Offerman), who has disbanded the FBI, leads an army of loyalists against the secessionist “Western Forces” of Texas and California. Florida has also formed its own breakaway faction, apparently.

The less one thinks about the logistics of Garland’s film, the better. What really matters is that WF forces are getting closer and closer to Washington, DC, with the President in their sights, and America has turned into a scorched battleground.

The clock’s ticking for our lead characters – celebrated war photographer Lee (Kirsten Dunst) and Reuters print journalist Joel (Wagner Moura) – who are determined to snag an interview with the President before he’s killed, even though it may cost them their own lives. We first meet them in New York City, covering a gathering for water rations that ends in a suicide bombing.

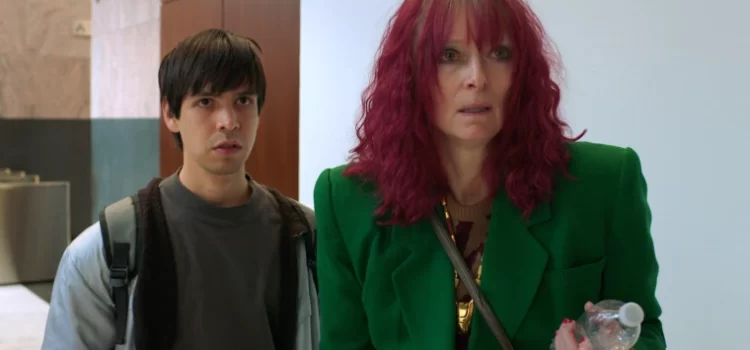

Lee encounters Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), a young, wannabe photojournalist, on the scene. Jessie idolizes Lee and wants to follow in her footsteps, while Lee feels uncertain about encouraging Jessie to become a photojournalist —even as she recognizes part of herself in Jessie that has long atrophied into cold professionalism.

Lee has spent her career documenting overseas conflicts, becoming hardened and haunted by the atrocities she’s witnessed – continuing to put herself in harm’s way for a potentially misplaced belief that her photos will mean something.

Joel, hard-drinking and charismatic, is fueled by a thrill-seeker’s urge to capture the next Big Moment. His sociability, contrasting with Lee’s, masks his own trauma and desensitization; he’s holding onto a sliver of boyishness through the nightmare.

Lee and Joel reluctantly agree to bring along aging New York Times writer Sammy (an ever-comforting Stephen McKinley Henderson) on their trip from NYC to DC. Sammy, out of shape and vulnerable though he is, is still drawn to danger and his craft. He acts as a pseudo father-figure for the group – helping guide them (to a point) through the various predicaments they run into along their road trip from Hell.

Jessie also weasels her way into the group thanks to Joel, much to Lee’s annoyance. Thus, the archetype-filled press squad begins their voyage across the heartland – encountering numerous terrors along the way, documenting them for the future, and grappling with their work’s purpose (or lack thereof) as an already-scarred America continuously slashes new wounds.

Indeed, Garland’s film is an uncomfortable, eerily prescient, and strangely entertaining experience. It’s difficult to look away from this nightmarish vision of a war on America’s soil, particularly given America’s current political tensions and fresh memories of the January 6 insurrection.

However, Garland avoids delving too much into the specifics of the conflict, and “Civil War” isn’t concerned with examining what led America to this point, or giving us a clear side to root for or against. The film tackles grander ambitions than just capitalizing on partisan hatred that anyone with an Internet connection can witness every day.

Rather, he presents a possible future where complete dehumanization of the Other runs rampant, and any hope for peace is shattered by self-perpetuating cycles of violence. Seen through the eyes of our central journalists, the film succeeds at both depicting their heroic sacrifices, as well as issuing a grim warning to viewers without providing easy answers.

Garland’s politically vague approach (he’s British, an outsider looking in) allows us to observe the horror without playing on or exploiting current offscreen tensions — an equalizing choice that renders the film’s graphic acts of barbarity all the more disturbing; startling and not sensationalized, every side is capable of cruelty.

Some viewers may decry the film’s both-sides-ism stance, but Garland’s film works better as a possible future taken to extremes, where negotiations and democracy have seemingly failed, and people have reverted to base instincts to cope.

As the characters variously become more numb, enraged, and even darkly energized by the situations they witness (massive shootouts, an idyllic Main Street patrolled by rooftop snipers, a bullet-ridden Santa’s wonderland), “Civil War” paints them as noble souls performing a necessary task, some of them mentally crumbling before our eyes.

Garland’s film, then, despite all its political side-stepping, stresses the importance of making their sacrifices and effort mean something, both within America and beyond it, within the film and outside of it. Garland puts the onus on us viewers to pay attention and to not merely let images wash over us as content to be consumed and forgotten, but rather as tools to be acted upon for change and action.

It’s a provocative, somewhat self-important message, one that has faith in cinema’s ability to affect hearts and minds, and its effectiveness depends on whether viewers are willing to pick up what Garland’s putting down.

Still, “Civil War” works on a more basic level, too, depicting complex characters on a visually striking journey full of suspense and tragedy with an occasional glint of gallows humor, each stop a new opportunity for taughtly-directed drama.

Rob Hardy’s gorgeous cinematography finds beauty in the desolation of familiar spaces — abandoned vehicles strewn across empty highways, suburban neighborhoods morphed into warzones, a forest aflame, and once vibrant, buzzing cities becoming eerily quiet, with the threat of violence lurking around every corner.

Combat sequences — enhanced by stellar sound work — are jolting and involving, going from cacophonies to silence as we sometimes abruptly cut to watching Jessie’s pictures develop.

The whole ensemble, too, is outstanding and has great chemistry, giving their characters a haunted gravitas. They embody, in distinct ways, a push/pull dynamic between documenting the truth and acting on innate empathy that might get them killed. Their contradictions only make them more compelling, rendering the film’s alternately cerebral and hectic rhythms powerful on both a large and small scale.

Dunst and Spaeny are particularly effective portraying characters that are seemingly mirror images of each other at different stages of their lives. Lee sees her former self in Jessie, a person who still has hope for the profession and for a better future, but witnesses first-hand Jessie’s growing desensitization — losing pieces of her youthfulness and, in some respects, her sense of self as she chases danger for the next shot.

Dunst gives an emotionally wrenching performance illustrating the shreds of hope and compassion that shine, if only briefly, through her tough exterior, while Spaeny sells Jessie’s arc without being melodramatic — Jessie bonding with the team as she comes into her own as the journalist she’s dreamed of becoming.

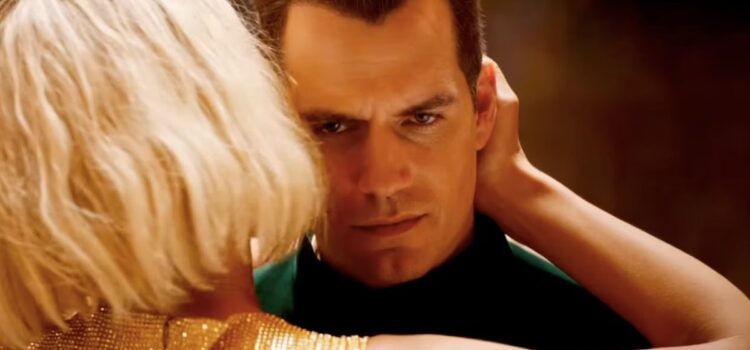

The film’s more memorable performance, though, is given by Jesse Plemmons as a member of a militia who’s as scary (if not scarier) than any recent horror movie monster, in a scene that’s difficult to shake.

Ultimately, “Civil War” is a gripping experience that will grow in power upon further reflection. It will no doubt spark heated debates — a feature that only great, necessary art can provide.

“Civil War” is a 2024 action science fiction film written and directed by Alex Garland and starring Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Cailee Spaeny, Sonoya Mizuno, and Nick Offerman. It is rated R for strong violent content, bloody/disturbing images, and language throughout, and runs 1 hour, 49 minutes. It opens in theatres April 12. Alex’s Grade: A.

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.