By Alex McPherson

Stylish, cerebral, and laced with pitch black humor, director David Fincher’s “The Killer” uses its deceptively simple narrative to uncover a thoughtful, albeit nihilistic, character study with a top-notch performance from Michael Fassbender.

Fincher’s film, based on a graphic novel by Alexis “Matz” Nolent, opens with a montage of various killing tools and settles on the titular nameless hitman (Fassbender), who is waiting for the right time to kill a wealthy target in Paris. He’s a cold, calculating, pretentious sociopath, who bides his time doing yoga, grabbing McDonalds, listening to the Smiths, reflecting on his craft, and waxing philosophical about the meaninglessness of existence, all while dressed (intentionally) like a German tourist.

His methodical elimination of targets is nothing personal; they’re little more than a speck in the pot of overcrowded humankind. He’s also devilishly resourceful, possessing seemingly limitless amounts of I.D.s with the names of ‘70s and ‘80s sitcom characters, and making use of all the modern conveniences and technology of our time (Amazon delivery stands out) to seamlessly weave throughout our world sans detection. If you see him, it’s already too late.

He’s set up in a WeWork space across the street from the target’s hotel room, since apparently (as his internal monologue explains) Airbnbs tend to have too many cameras. “Stick to the plan,” “Anticipate, don’t improvise,” “Empathy is weakness” are common phrases The Killer repeats to himself, closely monitoring his heart rate via FitBit to ensure maximum efficiency. He’s a well-oiled killing machine, a true master in the art of assassination. Until, well, he misses his shot, and takes out a sex worker instead.

The Killer makes a quick escape (thinking to himself “WWJWBD: What Would John Wilkes Booth Do?”), and the target gets to live another day. Goons are promptly dispatched to The Killer’s beachside house in the Dominican Republic — leaving his girlfriend, Magdala (Sophie Charlotte), within an inch of her life. Driven as much by revenge as by his own ego, our allegedly apathetic protagonist embarks on a globe-trotting mission to find out who’s responsible and murder them, plus any unlucky bystanders who get involved. But no matter what he tells himself, and his effectiveness at navigating our always-online reality, he’s still fallible: a monster thriving on delusion, insisting he’s above humanity while never being able to fully outrun his own.

Oscillating between suspenseful, shocking, and (dare I say it) laugh-out-loud funny, “The Killer” thrills and provokes from start to finish. This isn’t a particularly new story, but Fincher’s approach mines poignancy from a familiar template, immersing viewers into the mind of a villain and cutting him down to size — a character that’s easy to root against, but impossible to look away from, brought to life with Fincher’s characteristic panache.

Anyone who’s seen a Fincher joint before (“Fight Club,” “The Social Network,” or the regrettable “Mank,” for example) knows his films overflow with style, and “The Killer” is no different. Erik Messerschmidt’s crisp cinematography frames The Killer’s routine with distant, precise remove, sometimes blending him into shadows, to reflect his “professional” demeanor. The largely static camerawork changes to handheld as The Killer’s improvisational instincts kick in and panic rears its head.

Additionally, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s score pulses like a heartbeat as The Killer weaves through his surroundings like a parasite, evading detection at every turn, buzzing with discordant rhythms at moments of peril, such as during a cartoonishly destructive brawl later on that rivals the brutality of skirmishes in “John Wick: Chapter 4.”

Ren Klyce’s sound design is absolutely impeccable, with diegetic sounds (like the ring of an employee check-in kiosk or the bang of a ferry’s ramp locking into place) turned up to the max: nuisances that momentarily distract our titular assassin from his quest for vengeance. Suffice to say, the film is a sensory treat.

Fassbender’s performance is brilliantly tuned into the character’s cynicism and deliberate procedures. His stoic facial expressions belie a seemingly soulless husk — someone who’s devoted his whole life to his career without any interest or care for humanity, at least as far as he tells himself, but Fassbender subtly conveys his cracking facade as the story progresses.

His narration (from a strong screenplay by Andrew Kevin Walker) is sardonic, cruel, pop-culture-savvy, and at times very funny, but also reflective of his internal torment. His mantras are pushed to their limits, especially when interacting with unlucky bystanders in the wrong place at the wrong time. He has the skills to make it out of any deadly encounter, but at what cost?

Indeed, much of the unpredictability of “The Killer,” despite its familiar setup, comes down to contrast and dissonance. There’s something darkly comedic, and compelling, about being immersed into the mind of such a straight-laced character, observing his pain-staking preparations for the next hit, and seeing reality coming back to bite him, daring and/or forcing him to break from routine. Fincher plays around with this idea, too: moments of levity and endearment traditionally found in these types of stories aren’t present here; opportunities for redemption are tangled tantalizingly close and unceremoniously (often graphically) dashed.

Fincher barely spends any time with Magdala either — a non-issue because vengeance for her isn’t The Killer’s primary motivation. What really matters is maintaining his carefully cultivated lifestyle and self-image, scarred by his humiliating mistake in Paris that set this whole fight-for-life into motion. He knows the drill as well as anyone, but (through pride and desire to remain on the planet he has such apathy for) refuses to accept it.

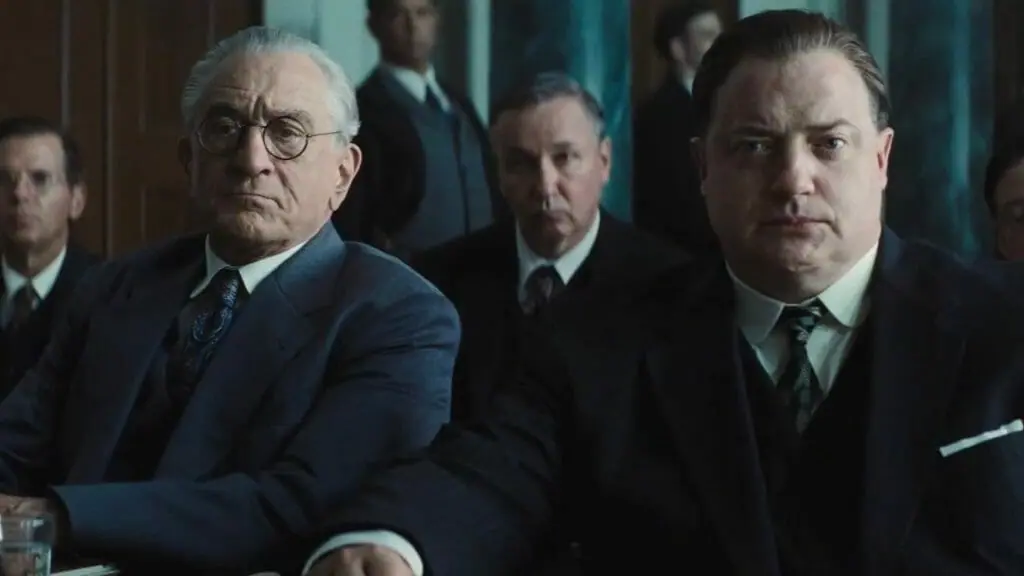

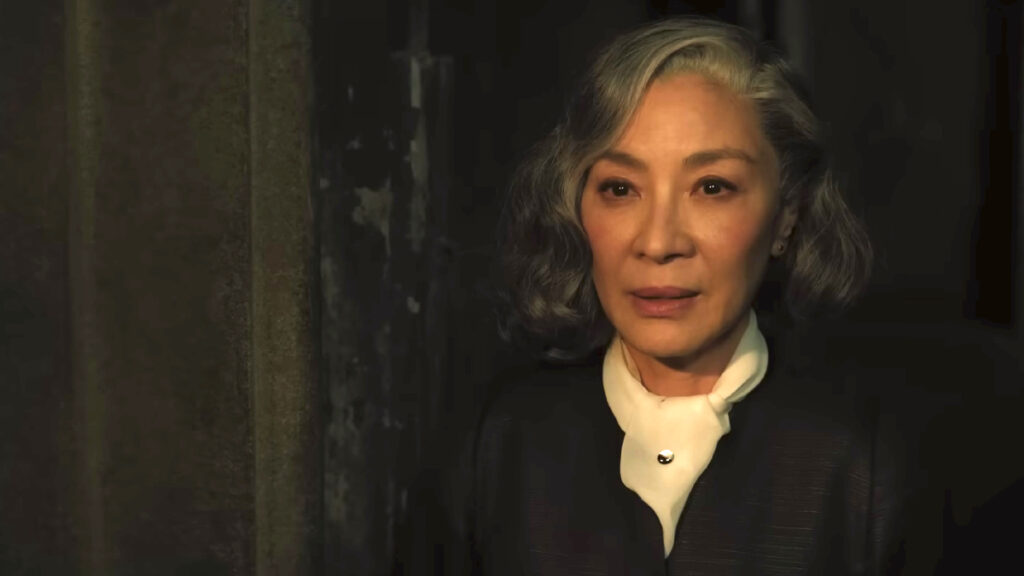

This idiosyncratic approach ensures that even if we think we know where “The Killer” is headed, we really don’t, not unlike the protagonist’s own predicament. Memorable appearances from Charles Parnell, Kerry O’Malley, and Tilda Swinton underscore this, unfolding in ways running the gamut of emotions.

Ultimately, “The Killer” is thrilling, amusing, and even moving to some degree, especially considering Fincher’s own reputation as a perfectionist. The Killer may have the tools to escape any situation, and maintain his own status, but can one really live without embracing life’s uncertainties?

This is one of 2023’s finest films thus far, much deeper than it initially seems, and deserving of the big screen treatment. Stick to the plan. Anticipate, don’t improvise. And don’t wait for Netflix, if at all possible.

“The Killer” is a 2023 action crime thriller directed by David Fincher and starring Michael Fassbender, Tilda Swinton, Charles Parnell and Kerry O’Malley. It is rated R for strong violence, language and brief sexuality, and runs 1 hour, 58 minutes. It opened in selected theaters on Oct. 27 and will stream on Netflix starring Nov. 10. Alex’s Grade: A+

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.