By CB Adams

Poor Carmen. As the protagonist in George Bizet’s 1875 opera, she’s sometimes reduced to being the poster person for critical analysis of gender dynamics and relationships.

Carmen’s character is often presented as some mixture of her as a free-spirited and independent woman who is simultaneously objectified and demonized (and ultimately murdered) for her sexuality. Then there are the issues related to Romani cultural representation and exoticism.

As a result, poor “Carmen.” As long as opera companies continue to mount productions of “Carmen,” they are going to beg these issues, including the normalization of toxic relationships like the one between Carmen and Don José that is marked by possessiveness, obsession and violence.

Oh, and add to these issues the way Bizet’s vibrant tapestry of unforgettable melodies and rich orchestration has been the victim of its own success. The drama and passion of Bizet’s dynamic and emotionally resonant soundscape, with evocative themes like the “Habanera” and the “Toreador Song” and their fusion of Spanish folk influences with classical operatic elements, have been hijacked by countless films, cartoons, commercials and television shows from “Looney Tunes” to “Bad Santa,” “The Simpsons” and “Gilligan’s Island.”

A lot has happened since 1875, and Carmen’s dual portrayal can be problematic in a contemporary context that seeks to dismantle harmful stereotypes and promote respect for women’s autonomy. Yet “Carmen” continues to be one of the most popular and frequently performed operas worldwide.

Its enduring appeal is reflected in the regular inclusion of “Carmen” in the repertoires of major opera houses and festivals, consistently drawing large audiences and receiving critical acclaim for its compelling music and dramatic storyline.

As someone who generally accepts John Ruskin’s notion that “art is in the expression, not the subject matter,” I can’t discount “Carmen” solely on the basis of some of its problematic attributes. Its emotional and imaginative qualities are part of opera’s DNA in particular and Western cultural heritage in general, and I believe that most opera-goers can see that the opera was of its time.

Modern productions of “Carmen” often attempt to address these issues through reinterpretation and modern settings. Directors and performers may emphasize Carmen’s agency and critique Don José’s behavior more explicitly. Some productions have even changed the ending to subvert the narrative of female victimization.

Not so with Union Avenue’s production, directed by Mark Freiman, and sung in the original French with English super-titles. This “Carmen” is a traditional interpretation that encourages a critical approach to understanding how the characters navigate a narrative fraught with jealousy, cultural clashes and fatal consequence.

Freiman, whose previous productions of “Carmen” have infused modern elements with fresh and contemporary elements, provides Union Avenue Opera with a more classic interpretation that remains true to the Bizet’s work and offers a restrained yet still poignant commentary on love, passion and the societal pressures that shape the characters’ destinies.

It achieves this by placing a bit more emphasis on the downfall of a straightforward Don José, torn between the sincere affection of his mother and his hometown sweetheart, Micaëla, and the seductive temptation of the morally unconventional Carmen.

Elise Quagliata in the role of Carmen brings a compelling and nuanced portrayal to Bizet’s iconic character. Known for her powerful mezzo-soprano voice, Quagliata’s interpretation of Carmen emphasizes her character’s boldness and independence and captures the character’s magnetic allure and defiance against societal norms.

Quagliata has tremendous stage presence filled with charisma and restrained dramatic flair. The same could be said for Brendan Tuohy as Don José, Joel Balzun as Escamillo, Joel Rogier as Moralés and Jacob Lassetter as Zuniga, but their individual performances do not cohere into a palpable chemistry, which is too bad.

This is one of this production’s significant weaknesses despite Freiman’s direction that explores the complexities of the characters’ interactions while attempting to clarify the psychological and emotional underpinnings of their actions. This is difficult to achieve when the main characters remain self-contained in their individual performances, not matter how well sung.

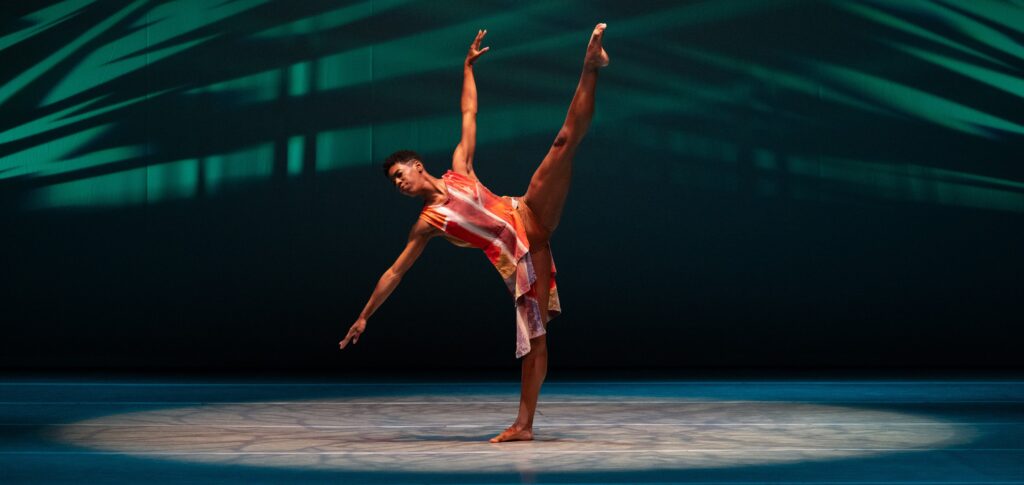

Quagliata is also this production’s choreographer. A good production of “Carmen” should enhance the storytelling and atmosphere of the opera. Quagliata’s choreography effectively conveys, with a light Spanish flair, the personalities and emotions of the characters, particularly Carmen.

In one moment, she confidently plants her leg on a chair. This is small but potent gesture. I haven’t seen a leg used to such great effect since the leg lamp scene in “A Christmas Story.” Another delightfully staged moment is the “cigarette girl” scene (played to great effect by the women of the chorus) as the factory workers puff and prance.

Quagliata’s choreography effectively synchronizes with Bizet’s music (performed vivaciously by the orchestra conducted by the always-excellent Scott Schoonover) and the stage design. Patrick Huber’s stage design provides an appropriate (if somewhat generic) backdrop that complements the characters’ movements across Union Avenue’s modestly sized stage.

Huber is also the lighting designer. During one of the two intermissions, the set’s two doorways were modified for the smugglers’ scene with what appeared (in the bright lights) to be vagina-like pelts. As the scene began, Huber’s atmospheric low light effectively created a subdued atmosphere – and the furry openings transformed into cave entrances. Oooh, what a little light design can do!

Tuohy presents a compelling Don José that highlights the character’s transformation from a dutiful soldier to a man consumed by obsessive love and jealousy. Tuhoy is strong but not brutish and presents his emotionally conflicted character with a palpable sense of longing and desperation.

Tuohy’s portrayal is characterized by a powerful tenor voice that effectively conveys Don José’s emotional turmoil and ultimately unacceptable violence. His stage presence and dramatic intensity bring depth to the character, even if not to the ensemble as a whole.

One of the standout performances is provided by Meroë Khalia Adeeb as Micaëla. Adeeb delivers a character that embodies innocence and fidelity while navigating the opera’s moral landscape with her steadfast love for Don José. Adeeb’s rich and resonant voice captures the character’s gentle nature and inner strength, and the rest of performance hits all the right notes: flexibility and emotional range, expressiveness and technical skill that is precise and controlled.

Her performance of Micaëla’s most famous aria, “Je dis que rien ne m’épouvante” (I say that nothing frightens me), was heartfelt, determined and poignant.

Also commendable is the performance by Xavier Joseph as the smuggler Le Dancaïre. The role is a secondary character, but Joseph delivers his character with physicality, wit and bonhomie.

And while on the topic of fun, this production includes two scenes with controlled mayhem and exuberance provided by a delightful children’s chorus.

Lassetter presents his Zuniga with a big-throated blend of authority and moral ambiguity and a performance that captures the character’s commanding presence and underlying conflict. Rogier’s Moralés is equally strong. Rogier exudes a robust and confident demeanor that emphasizes his steady, grounded nature and his role of Moralés’ as a foil to Don José.

Balzun provides an acceptable Escamillo, the bullfighter. The role of Escamillo demands a charismatic singer who embodies traditional masculinity through physicality and social admiration and serves as a foil to Don José. Balzun delivers a Escamillo who is a pompous yet effete man.

“Carmen” continues at Union Avenue Opera through July 13. For more information, visit: www.unionavenueopera.org

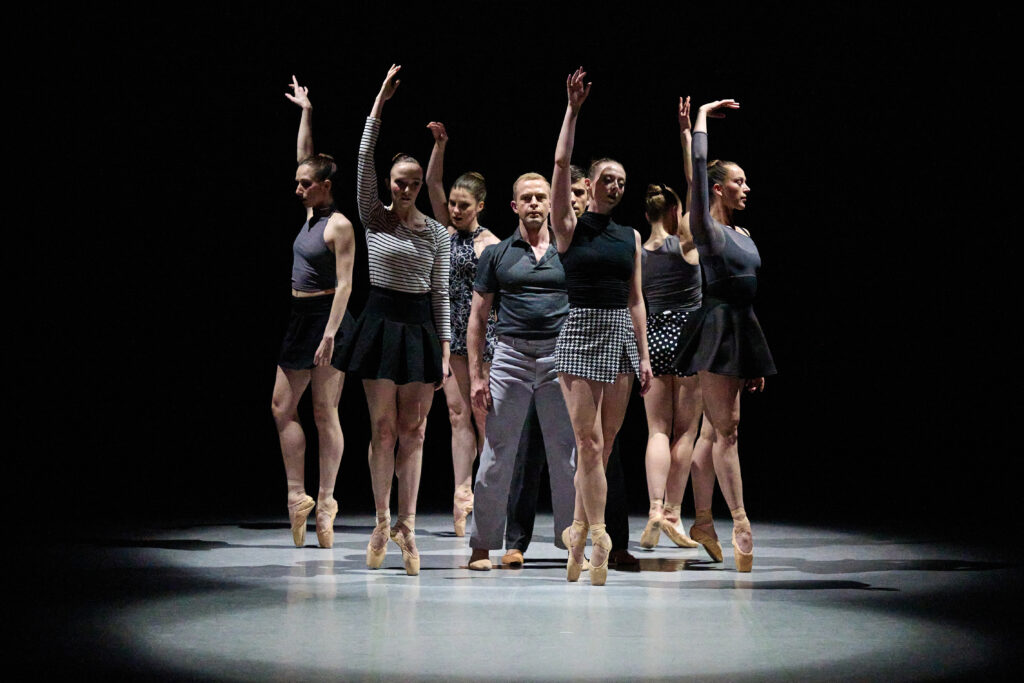

Youth Ensemble : Lucca Badino *, Bryce Cleveland *, Blaise Magparangalan *, Chloe Melton, Nora Moss *, Lila Treuiller *, Louis Wang *, Tristan Williams * (not in order). Photo by Dan Donovan.

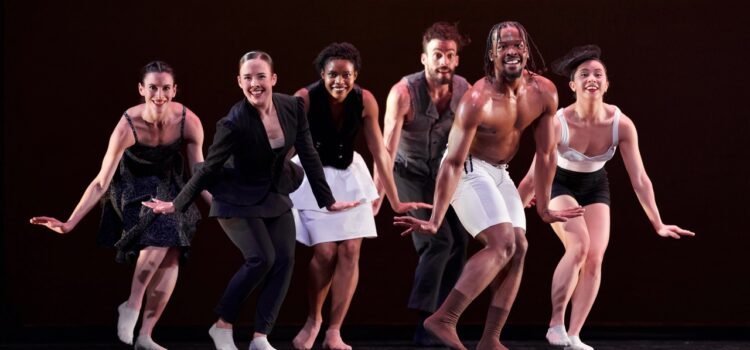

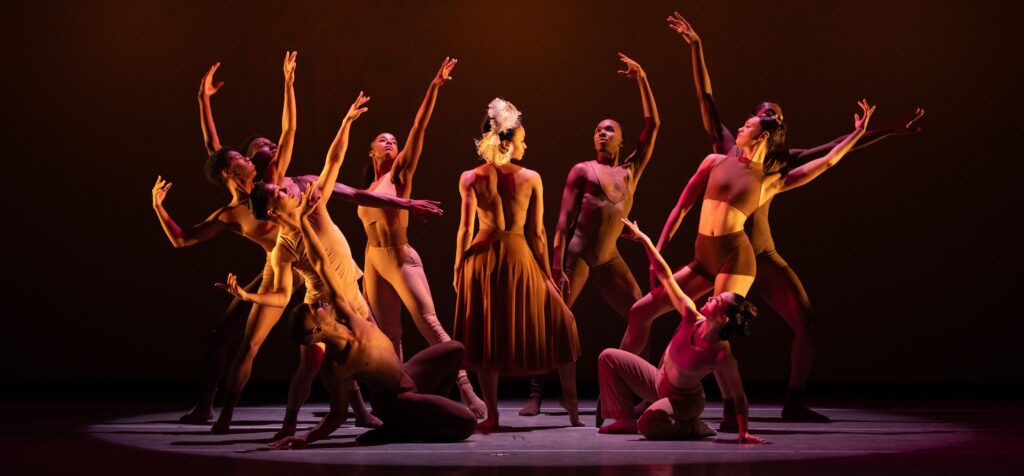

Cover photo: Holly Janz, Marc Schapman, Elise Quagliata, Xavier Joseph, and Gina Galati/ Photo by Dan Donovan.

CB Adams is an award-winning fiction writer and photographer based in the Greater St. Louis area. A former music/arts editor and feature writer for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, his non-fiction has been published in local, regional and national publications. His literary short stories have been published in more than a dozen literary journals and his fine art photography has been exhibited in more than 40 galley shows nationwide. Adams is the recipient of the Missouri Arts Council’s highest writing awards: the Writers’ Biennial and Missouri Writing!. The Riverfront Times named him, “St. Louis’ Most Under-Appreciated Writer” in 1996.