By CB Adams

Union Avenue Opera’s production of “Into The Woods,” stage directed by Jennifer Wintzer, is a rich tapestry. From the set design through the final song, you (figuratively) want to run your hands over the texture and enjoy its quality.

Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine are the weft and weave, but it’s way UAO finely stitches the musical’s balance of humor and humanity with death and disillusionment that delivers a sumptuous and reassuring tapestry – like a Bayreux or Unicorn come to life.

UAO earns these accolades for its season-ending production of “Into the Woods” with excellence in all the theatrical components: direction, staging and set design, costumes and cast performance. If you’re a Sondheim fan but have never attended a UAO performance, don’t let the word opera scare you off. They deliver a traditional interpretation of this classic without any elaborate or ornamental operatic embellishments.

If you’re an opera fan, UAO always ends its season with an operetta or musical. Last year, they concluded the season with a fine production of “Ragtime.” Many opera companies do this, such as the storied New York City Opera, and it’s a way to demonstrate how opera set the stage for subsequent musical theater iterations. It’s also a way to fill the seats.

The first – and one of the most impressive – aspects of this “Into The Woods” is the stage design by Laura Skroska, whose work on UAO’s production of the moody, atmospheric “Turn of the Screw” set was one of last year’s best. For “Into The Woods,” Skroska’s vision evoked the magical and eerie atmosphere of this fairytale world.

She, along with scenic artist Lacey Meschede and set decorator Cameron Tesson, maximized the use of the Union Avenue Church’s modest stage by filling it with mossy tree trunks that serve as posts to multiple, rising platforms. The set extended into the sanctuary with the balcony festooned with moss and other elements from the main stage. The balcony also served as Rapunzel’s tower and the home of the heard-but-not-seen giants of Jack and Beanstalk fame.

Before the show began, the set created the ideal visual preparation for the rest of the performance. Skroska’s design elements — expertly and effectively illuminated by Patrick Huber – underscore the timeless and complex nature of Sondheim’s work, ensuring that the woods felt both enchanting and foreboding, perfectly complementing the story’s themes.

Further enhancing the production are the outstanding costumes by Teresa Doggett. Appropriately tatty and fairytail-ish, Doggett’s costumes play a pivotal role in elevating “Into The Woods” by enhancing the visual storytelling and deepening the understanding of each character’s journey through the intertwined storylines. They reflect the dark, whimsical aspects of the show while paying homage to the traditional fairytale origins.

The movie adaptation of “Into the Woods” could use Disney magic to conjure the special effects. On stage, it’s a bit more challenging. UAO’s production makes fine use of the talents of puppeteer Jacob Kujath to portray Milky White, the emaciated cow, and a flock of birds. The use of these puppets adds a whimsical and imaginative element to the production. Kujath brings them to life through expressive manipulation and playful interactions that seamlessly integrate with the live action.

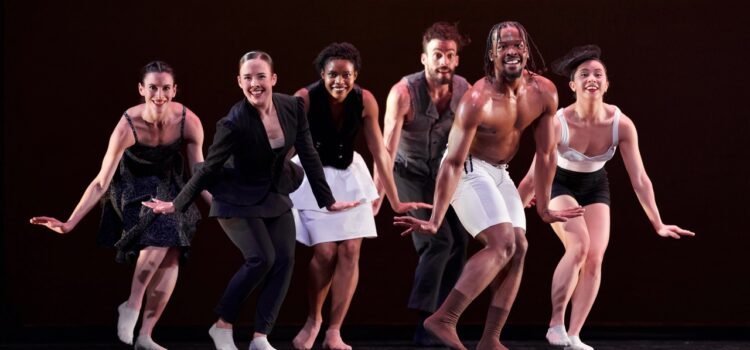

The cast of 21 showcases the depth and versatility across the roles with performances that rise from solidly good to exceptional. That latter response is earned by mezzo-soprano Taylor-Alexis Dupont for her Witch. Clad in a wickedly good mask, which is almost a character unto itself, Dupont intensely inhabits the character of the Witch and delivers an impressive performance.

It is a sheer delight witnessing Dupont – through powerful song and acting – deliver a full transformation of the Witch, exemplifying the duality of her character. Her believable duality turns “Children Will Listen” into an emotional, cautionary swan song delivered by a once-menacing – but now tragic – figure.

“Into The Woods” isn’t all serious and dark. At the other end of the spectrum from the Witch are Rapunzel’s and Cinderella’s respective, rather vacuous princes, played by tenors James Stevens and Matthew Greenblatt. Their duet “Agony” is usually one of the top-three most favorited songs, and Stevens and Greenblatt do not disappoint in their delivery of this biting, satirical tune.

Sidenote: “Into the Woods” debuted in 1986, and Cinderella’s dum-dum prince with his “I was raised to be charming, not sincere” attitude is definitely a precursor, if not the model, for the Ken character in the recent “Barbie” movie.

Soprano Brooklyn Snow’s portrayal of Cinderella her vulnerability with a growing strength, effectively conveying her journey from innocence to self-awareness through both subtle acting and dynamic vocals. Likewise, soprano Leann Schuering’s Baker’s Wife successfully merges the character’s fairy-tale origins with the weight of her decisions.

Schuering’s performance is marked by its depth and emotional resonance. Soprano Laura Corina Sanders performance of Little Red Ridinghood [sic] captures the character’s innocence and curiosity and skillfully transforms from naive cheerfulness to a deeper understanding of the dangers and complexities of the world.

Baritone Brandon Bell bakes into his performance as the Baker a balance of warmth with emotional complexity. Like the Witch, he too undergoes a transformation. Bell’s expressive acting and strong vocals make transition from reluctant hero to a more self-assured character both relatable and compelling.

Another baritone – a base baritone – Eric McConnell, delivers another highlight performance as the Wolf, with a blend of seductive charm and menacing undertones. McConnell’s deep voice projects exceptionally well into the sanctuary and masterfully balances the Wolf’s allure and danger with “Hello Little Girls” – a song that could come off as “pervey” with a less skilled performance.

Christopher Hickey plays both the Narrator and the Mysterious Man. Perhaps because the demands of each character are different, the Mysterious Man is the better of Hickey’s performances because there is more opportunity for him to inhabit the character, which he does by subtly weaving together intrigue and depth to create a profound and haunting presence.

On opening night, the weakest element of this otherwise satisfying performance was the imbalance of the sound, especially during the first half. The unamplified voices, especially those of the female performers, were repeatedly overwhelmed by the orchestra.

This performance includes supertitles, but with a musical in English, they shouldn’t be necessary to hear what’s going on. This made for a frustrating experience, leaving one wishing to “turn up” their volume a click or two to better enjoy the quality of the singing and dialogue.

This feeling was further exacerbated because the orchestra, under the direction Scott Schoonover, superbly performed the score. It would have been a shame to miss a single note. Perhaps because adjustments were made during the intermission, the sound issue was almost eliminated in the second half.

Another side note: From Greek myths to Joseph Campbell’s “The Hero’s Journey,” Carl Jung’s psychology and the fairytales of the Brothers Grimm, the “dark woods” are often inhabited by archetypal patters and are a place of confusion, danger or the unknown where the hero or heroes confront trials and their shadow selves.

Sondheim and Lapine created a masterful musical that hews closely to the cautionary purpose that fairytales were designed to convey. This cannot be a musical with an empty, happily-ever-after ending. UAO’s production effectively – and accurately – delivers an ending that should leave the audience feeling reflective, with a palpable poignancy that underscores the idea that while fairy tales may end, the journey of growth and understanding continues. It takes two acts and a lot of songs to reach that point.

Union Avenue Opera’s “Into The Woods” plays August 16-24. Visit unionavenueopera.org for more information.

CB Adams is an award-winning fiction writer and photographer based in the Greater St. Louis area. A former music/arts editor and feature writer for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, his non-fiction has been published in local, regional and national publications. His literary short stories have been published in more than a dozen literary journals and his fine art photography has been exhibited in more than 40 galley shows nationwide. Adams is the recipient of the Missouri Arts Council’s highest writing awards: the Writers’ Biennial and Missouri Writing!. The Riverfront Times named him, “St. Louis’ Most Under-Appreciated Writer” in 1996.