By Alex McPherson

At its best when fully leaning into uninhibited mayhem, director Sam Raimi’s “Send Help” is a knowingly loony, if broad, satire elevated by Dylan O’Brien and a deviously crazed Rachel McAdams.

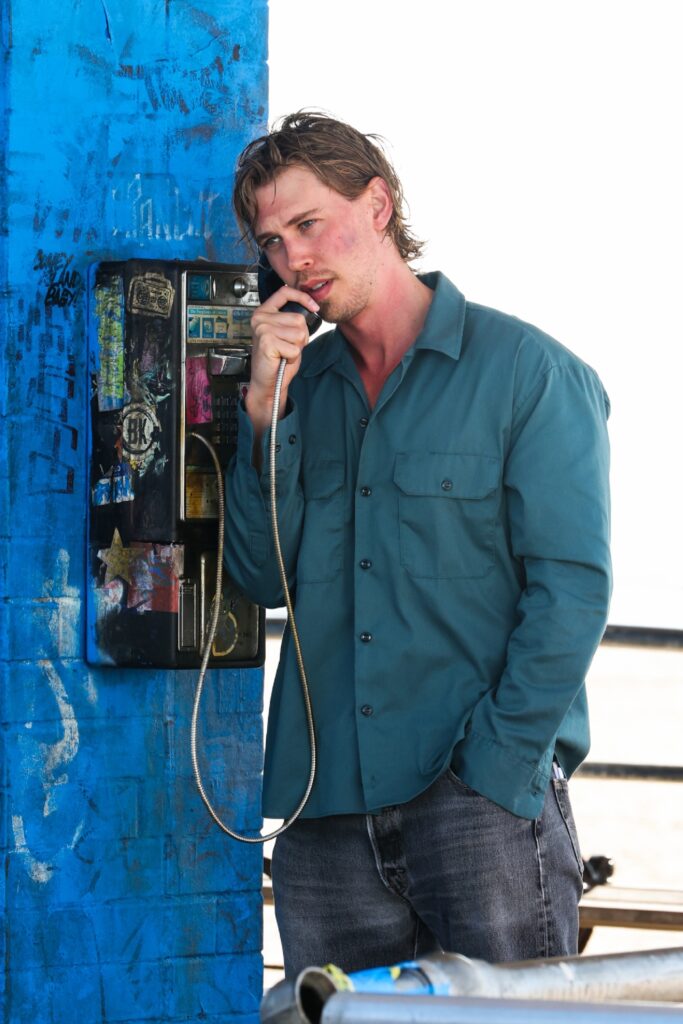

We follow Linda Liddle (McAdams), a nerdy, socially awkward, yet skilled longtime employee at a consulting firm who — despite being far more knowledgeable at her job than the slick-haired men that surround her — is underappreciated. She doesn’t have many friends and most of her meaningful conversations are with her pet cockatoo.

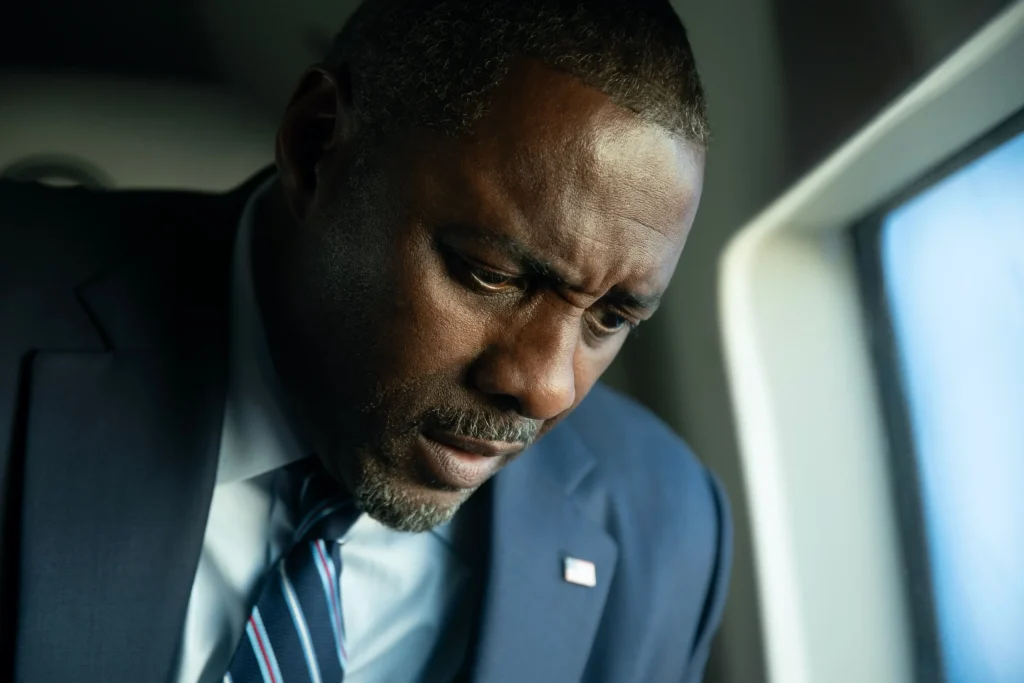

She’s also a trained survivalist and has recently applied to be a contestant on the reality show “Survivor.” Linda hungers for more recognition, and the company’s CEO Franklin Preston (Bruce Campbell) recently promised her that she’d be Vice President one day. Preston has suddenly passed away, though, and the reins of the company fall to his son Bradley (Dylan O’Brien), who has zero interest in following through on his father’s promise.

Bradley, pompous and sexist, is repulsed by Linda’s appearance and efforts to assert herself. Instead of promoting her, he installs fellow frat brother and golfing buddy Donovan (Xavier Samuel) as VP. As consolation before firing her for good, Bradley gives Linda one last assignment to “prove herself” by traveling with his boys club to Bangkok to close a major merger — she is an expert number-cruncher, after all.

While aboard the private plane en route, Linda toils away on a work document. Bradley and his bros are not working; instead they are watching Linda’s “Survivor” audition tape and loudly snickering.

Before Linda finally snaps, a violent thunderstorm sends the plane spiraling into the ocean, killing everyone onboard in gratuitously violent (and, admittedly, quite funny) fashion. Linda barely survives and washes ashore on a nearby deserted island — a prime place to make use of her survivalist skills.

Bradley also survives and washes ashore (with a messed-up leg). Despite continuing to treat Linda terribly, he realizes that he needs her to live. Linda takes almost too much pleasure in this new power dynamic and lifestyle; it’s unclear whether she wants to be rescued at all.

Both Linda and Bradley harbor persistent hatred towards each other despite their burgeoning friendship. As the days pass, tensions escalate, as both of these damaged souls vie for dominance over each other through bloody one-upmanship.

What begins as a rather tame dramedy evolves into something much gnarlier and more cynical. “Send Help” isn’t a revolutionary film, and it doesn’t have anything particularly incisive to say, but it’s a nasty and enjoyably twisted return to form for Raimi. It wouldn’t work anywhere near as well without O’Brien and McAdams’ sheer devotion to every twist and turn.

McAdams in particular really sells this heightened premise. Mark Swift and Damian Shannon’s screenplay sends her on quite the journey from meek nerd to resourceful leader to someone who has fully lost her marbles. It’s great fun watching McAdams lean into Linda’s quirks and neuroses, bringing a happy-go-lucky energy that’s just as quick to stab you in the back (or anywhere on the body).

We want Linda to succeed and get her revenge against Bradley, but part of the twisted fun of “Send Help” is exploring just how far she will go, and how long we’re willing to support her along the way.

O’Brien is pitch-perfect as the smug man-child Bradley, who couches nearly every “dialogue” with a patronizing, better-than-thou tone. Swift and Shannon’s script does an excellent job portrayinging the ways that power-hungry bosses treat their employees, making even Bradley’s most callous moments ring true.

Of course, watching Bradley become wholly dependent on Linda for his survival is satisfying; yet, as “Send Help” reiterates repeatedly, there’s no easy way to resolve their deep-seated mutual hatred.

Raimi’s film is difficult to pigeonhole within a single genre. “Send Help” is a playful, tonally-all-over-the-place experience, with elements of classic adventure films (Danny Elfman’s score feels like something from Hollywood’s Golden Age), strange forays into romcom territory, and Raimi’s signature horror flourishes.

It’s an odd amalgamation that doesn’t always work — the beginning, in particular, is far less tightly edited and stylistically engaging than the island shenanigans, and the will-they-won’t-romance that comes into play heads down predictable paths. So, too, does the big “twist,” which waters down some of the film’s more pointed ideas on gender power dynamics for a far more schematic, underwhelming framework.

With Raimi at the helm, you know he won’t hold back on the over-the-top carnage, editing, and camerawork. Bob Murawski’s editing and Bill Pope’s cinematography perfectly complement Raimi’s sensibilities — match cuts, crazy zooms, POV shots of feral boars, it’s all there, along with buckets of goopy gore and a couple of genuinely squirm-inducing moments that are difficult to unsee (literally).

The film just takes a while to get to those “Holy Shit!” moments, spinning its wheels at times repeating the push-pull dynamic between Linda and Bradley, as defenses are lowered and, soon after, raised again.

But pacing and plotting issues aside, “Send Help” is still a perfect film to watch in a crowded theater, seeing these characters regress as the outside world crumbles around us.

“Send Help” is a 2026 horror film directed by Sam Raimi and starring Rachel McAdams, Dylan O’Brien, Bruce Campbell, and Xavier Samuel. It’s run time is 1 hour, 53 minutes, and it is rated R for strong/bloody violence and language. It opened in theatres Jan. 30. Alex’s grade: B.

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.