By Alex McPherson

With Harrison Ford lending emotional grandeur to an otherwise middling adventure, director James Mangold’s “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny” provides an acceptable finale for the iconic character.

Indy’s latest outing begins in the mid-1940s, with the end of World War II in sight, as a heavily de-aged Indy (always looking “off”) and his trusty academic pal Basil Shaw (Toby Jones) attempt to recover stolen artifacts from Nazis. After Indy escapes capture due a conveniently deployed airplane bomb and KOs plenty of the monstrous chaps, he races onto a train (after a dimly lit, CGI-reliant car/motorcycle chase) containing the Lance of Longinus — a blade supposedly containing traces of the blood of Christ — and an also-captured Basil.

Among the evildoers is Nazi physicist Jürgen Voller (Mads Mikkelson), a nefarious soul aboard the train who’s in possession of one half of the Antikythera — a dial created by Archimedes that supposedly allows for time travel should both halves be combined. Bloodlessly bombastic violence ensues, concluding with a battle atop the train that results in Voller thwacking his head on a pole and Indy and Basil jumping into a lake below, Antikythera in hand.

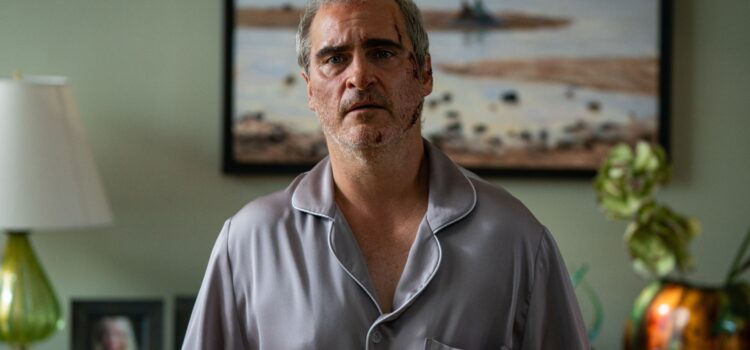

Flash forward to 1969, and our titular hero is in dire straits. Grumbling around his messy New York City apartment after having recently separated from his wife, Marion (Karen Allen), and with his son, Mutt (Shia LaBeouf) out of the picture, Jones is a shell of his former self, lacking purpose and direction as he prepares to retire from teaching archaeology at Hunter College. The Apollo 11 astronauts have just returned home, and society is looking to the future, rather than the past that Jones has devoted his life to. He’s become a curmudgeon, lacking the adventurous spirit he once had, both due to his age and regrets that torment his psyche.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, he soon runs into Basil’s daughter, Helena (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), who’s after the Antikythera and wants to continue Basil’s life’s work of finding the missing half (or so she initially claims: she’s a hardcore capitalist eager to make a buck). After tricking Indy, she runs off with the artifact, while also being pursued by the returning Voller and his cronies, including Shaunette Renée Wilson as a crooked CIA agent and Boyd Holbrook as a take-no-prisoners killer.

Thus begins a globe-trotting romp from New York to Tangiers to Athens to Sicily, as Indy, Helena, and Helena’s youthful sidekick Teddy (Ethann Isidore) attempt to find the remaining half of the Antikythera before the Nazis get their hands on it and change the war’s outcome. Indy’s back for another go around, just like old times, with plenty of returning faces and fantastical shenanigans at play.

Indeed, “Dial of Destiny,” the franchise’s first installment without Steven Spielberg at the helm, leans hard into nostalgia at the expense of dramatic punch — although copious literal punches are thrown. Mangold’s film (at nearly 2.5 hours) is a strange beast: at once comforting in its embrace of old-fashioned thrills, but averse to taking any real risks with Indy himself. Ford’s soulful performance is still able to overcome the screenplay’s frustrating lack of focus, buoying what is otherwise a slightly-above-average experience featuring lackluster set-pieces and formulaic plotting.

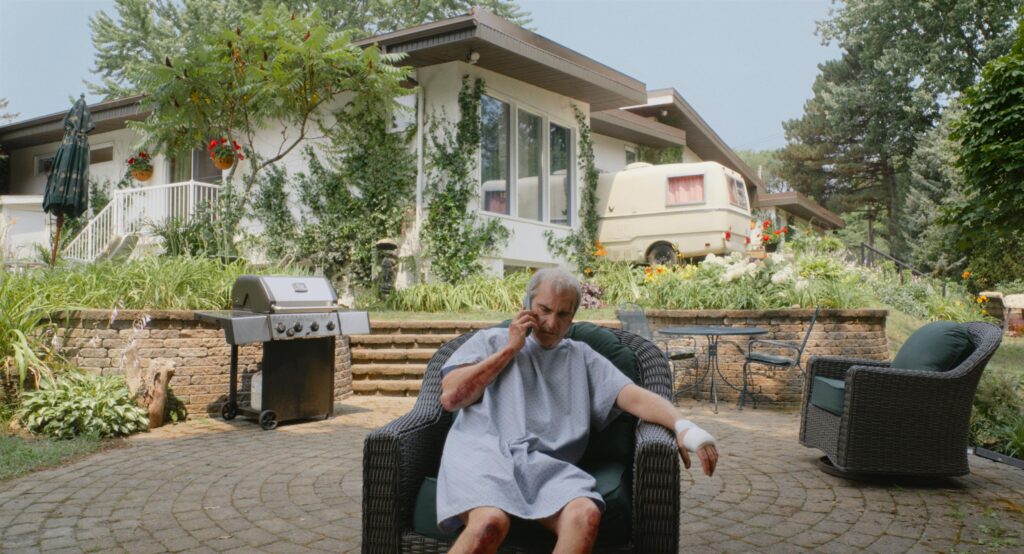

With his iconic whip, fedora, and witty remarks, Ford continues to excel in the role — conveying a wide range of emotions with lived-in gravitas. His portrayal deserves a stronger film to support it; we can see his sadness, guilt, and mournful reflection in pivotal scenes, along with his mischievous, daring old self bubbling back to the surface. Most everything between Indy’s scenes of introspection is fairly by-the-numbers — with little that stands out beyond a ludicrous conclusion, which, without spoiling anything, goes down a zany rabbit hole. It remains great to see Ford back in the saddle nevertheless.

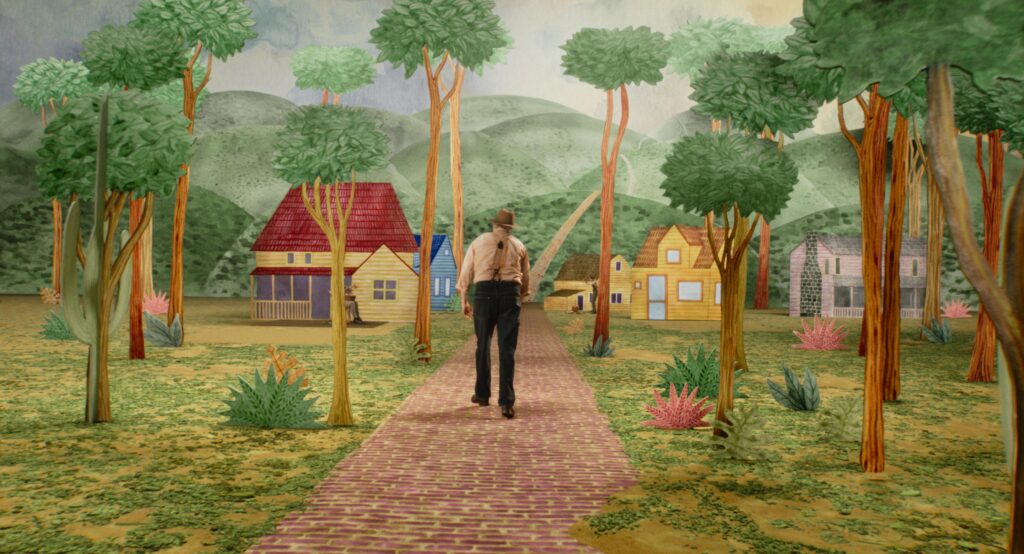

While “Dial of Destiny” attempts to recapture the old-school thrill and “feel” of the series’ previous installments (complete with cameos, visual motifs, and eels taking the place of snakes), Mangold’s approach robs time from developing Indy as a character. Mangold’s reliance on nostalgia may well be the point, but reminding viewers (and Indy himself) of the series’ former glory shifts focus from the here-and-now: the antics in search of the dial (which could, theoretically, permit Indy to rectify wrongs in his own sad life) resort to familiar tropes and payoffs, neglecting to innovate on tradition to tell a consequential story about Indy’s place in the world today.

The film seemingly emphasizes the importance of not living in the past, but using remembrance as a means of personal growth. This might be meaningful to Indy, but the plot stemming from that idea is a workmanlike imitation on what’s come before — far from bad, but not making a lasting impact.

Waller-Bridge, at least, shines as a brash, sarcastic, independent woman whose allegiances are often in question. She’s after the dial not only in the hopes of one day selling it for a boatload of cash, but also by a sense of wanting to continue her father’s lifelong work; the need to explore passed down from one generation to the next. By the end, her arc is a bit muddled, given her internal tug-of-war between cynicism and earnestness, but she’s still a worthy companion, and holds her own in the copious CGI-laden action sequences. Mikkelson’s Voller doesn’t stand out as particularly interesting, at no fault of the performance: he’s just a standard, franchise-typical baddie, accompanied by likewise generically sadistic goons.

Speaking of action, the 80-year-old Ford obviously can’t do much stunt work nowadays, requiring computer wizardry to do the heavy lifting. It’s too bad the majority of sequences are so cartoonishly over-the-top and confusingly framed. Despite all the carnage on display (including during the intro, a horse chase through an NYC parade, and a frantic tuk-tuk pursuit through a Tangiers market), they’re often weightless, chaotic, and lacking the rhythm that Spielberg’s direction lent them, barring some amusing visual gags that remain a series staple. Yet again, “Dial of Destiny” tries to live in the past, altering reality to present scenarios that would likely have worked better in the animation medium altogether.

It’s a testament to Mangold’s competency and Indy’s sheer likability that “Dial of Destiny” is still an enjoyable watch regardless of issues. John Williams’ score delivers the goods (as always), and Mangold’s stylistic tributes to Spielberg give the film energy even when the story comes up short. Combined with Ford’s exceptional performance and fan service callbacks, “Dial of Destiny” is worth watching, if not something that significantly adds to the adventurer’s legacy.

“”Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny” is a 2023 action-adventure directed by James Mangold and starring Harrison Ford, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Mads Mikkelson, Karen Allen, Antonio Banderas and Boyd Holbrook. It is Rated PG-13 for sequences of violence and action, language and smoking and runs 2 hours, 34 minutes. It opens in theaters June 30. Alex’s Grade: B-.

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.