By Alex McPherson

Silly, messy, yet filled with provocative ideas and starring an already classic antagonist, director Gerard Johnstone’s “M3GAN” is one of 2023’s first great films.

Set in near-future Seattle, “M3GAN” centers around Gemma (Allison Williams), a robotics engineer working for a toy company called Funki developing flatulent, Furby-esque “Perpetual Petz.” Gemma, a workaholic bordering on a mad scientist, has higher aspirations — creating a lifelike artificial intelligence that can serve as a child’s loyal companion, assisting with parental duties for guardians unwilling or unable to put the effort in themselves.

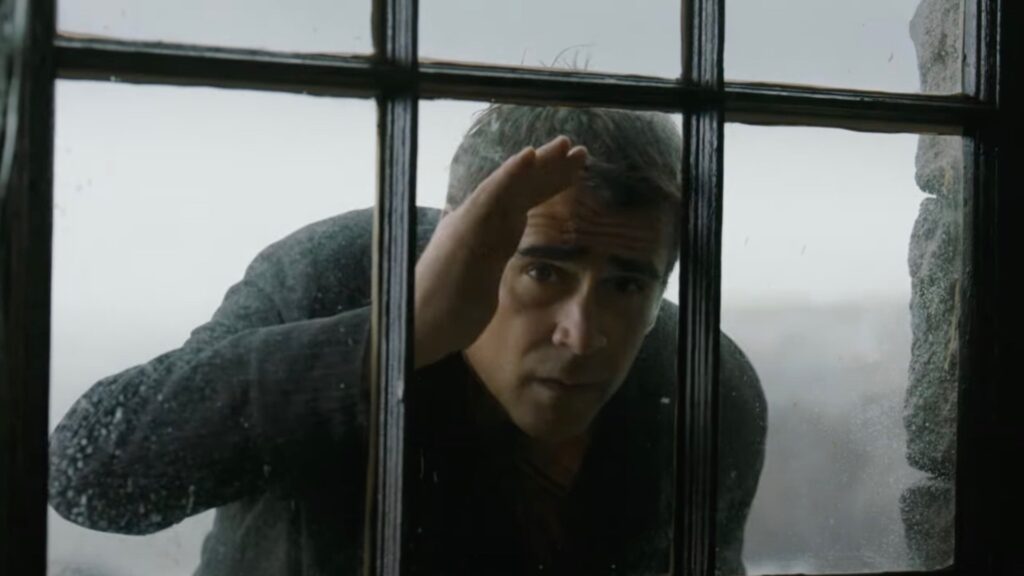

After a prototype demonstration goes haywire, her brash, overeager boss, David (Ronny Chieng), demands Gemma and her team construct a less complex version of Perpetual Petz to fight the competition. All hope for Gemma’s obviously flawed passion project goes out the window… until a fateful circumstance gives her the opportunity to pursue her dreams.

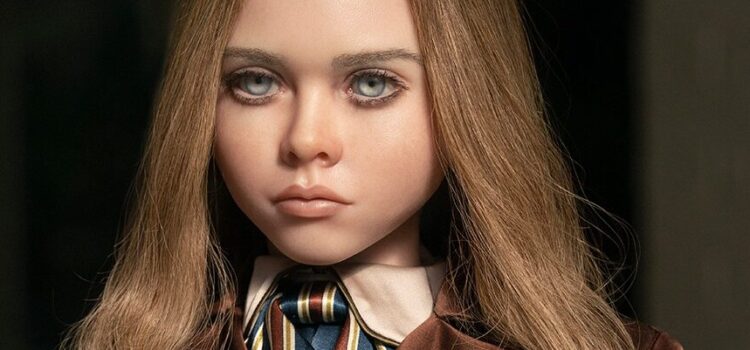

Her niece, Cady (Violet McGraw), is orphaned in a car accident involving a snow plow that kills both her parents. Gemma is called upon to assume guardianship of Cady, but she has absolutely no idea or willingness to interact with her on a meaningful level. Fortunately, or, rather, unfortunately, she finally has an excuse to build her Frankenstein once again — creating the titular M3GAN (Model 3 Generative Android), a wry and viciously programmed android with the body of young girl, a mean side-eye, off-kilter movements, and a propensity to sing pop songs — to provide for Cady and give Gemma the freedom to go about her own, separate life.

Cady’s attachment to M3GAN grows quite extreme, however, as does M3GAN’s directive to protect her at all costs, definitely not above killing anything that inconveniences her. The bodycount builds, Gemma faces increasing pressure from David to show M3GAN off to the world, and she must learn to take responsibility for her creation and, potentially, for her own life.

Despite relevant commentary on humankind’s dependence on technology, companies’ ruthless exploitation of our personal lives to sell goods, and how mistreatment of a near-sentient AI can heinously backfire, “M3GAN” is, at its core, a batshit insane slice of PG-13 horror that never takes itself too seriously. This is a satirical comedy above all else, eschewing nuance in favor of putting its Mean Girl to savage work.

M3GAN, voiced with cheerfully malevolent gusto by Jenna Davis and physically performed by Amie Donald, mixing stiltedness with bursts of animalistic energy, is quite the character. She’s both creepy and hilarious, eliciting nervous laughter with practically every one of her sardonic quips. Johnstone, screenwriter Akela Cooper (who also wrote 2021’s off-the-rails “Malignant”), and story co-creator James Wan aren’t here to necessarily humanize M3GAN, but they emphasize the poor ways she’s treated in this morally bankrupt world. M3GAN’s merely following her programming — serving Cady to the best of her reductive, frightening abilities — and gradually developing self-awareness of her own, fighting for her independence and a misguided desire to control, rather than be controlled. M3GAN is often discarded as an “other” to reside among other toys, or literally powered down whenever push comes to shove.

Peter McCaffrey’s cinematography mines this idea to darkly comedic effect; one memorable shot at a school field day features M3GAN seated in the middle of a pile of stuffed animals, glaring at the camera as if to say how could you treat me this way? When she’s unleashed to wreak her (largely bloodless) havoc, you might almost root for her as she disposes of those who disrespect and use her for their own selfish advancement.

The more (traditionally) human characters aren’t nearly as engaging, but Williams and McGraw lend pathos even in the most ludicrous stretches. Williams excels at delivering the film’s deadpan dialogue — Gemma’s awkwardness and impulsivity almost feel robotic at certain points, as she struggles to navigate her newfound maternal role and care for the grief-stricken Cady. Her arc later on in the film seems rushed (gotta get back to M3GAN dancing, after all), but Gemma’s learned empathy hits home with surprising, albeit not exactly poignant, force.

McGraw shines as Cady, conveying ample dramatic range as proceedings unfold. M3GAN seemingly fills the void left by the loss of her parents, and Cady refuses to be separated from her. She can have any question answered, a playmate always by her side, and someone to protect her from harm. Despite M3GAN’s increasingly violent actions, Cady remains strongly loyal, addicted to a “solution” that, despite how it’s promoted, is a dangerous rabbit hole.

Side characters — with the exception of David, who gives Chieng plenty of opportunities to ham it up as a shameless executive who wouldn’t feel out-of-place in a “Saturday Night Live” sketch — are mainly there as fodder for M3GAN, but that’s exactly what the film calls for. Although the PG-13 rating prevents Johnstone from fully cutting loose, there’s still a couple of wince-inducing moments (one involving not-quite-surgical ear removal) that won’t leave my mind anytime soon. Indeed, “M3GAN” pulls no punches when it counts.

The bombastic finale reverts to familiar tropes, and the combination of thoughtful commentary with goofiness doesn’t click together “smoothly,” but that adds to the charm. “M3GAN” remains an unabashedly fun watch, comfort food for those willing to update to its zany wavelength.

“M3GAN” is a 2023 science-fiction horror comedy directed by Gerard Johnstone and written by Akela Cooper. It stars Allison Williams, Violet McGraw, Ronny Chieng, Amie Donald, and Jenna Davis. It is rated PG-13 for violent content and terror, some strong language, and a suggestive reference, and the runtime is 1 hour, 42 minutes. It opened in theaters January 6. Alex’s Grade: B+

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.