By Alex McPherson

Director Jane Schoenbrun’s “I Saw the TV Glow” is a dreamlike, thought-provoking, and emotionally gutting experience that’s at once personal and universal — an exploration of loneliness, art, escapism, and repression within a reality that’s its own kind of nightmare.

The year is 1996. We follow Owen (first played by Ian Foreman, then Justice Smith), a seventh-grader in a small, nondescript suburb that Shoenbrun frames like a dreary purgatory.

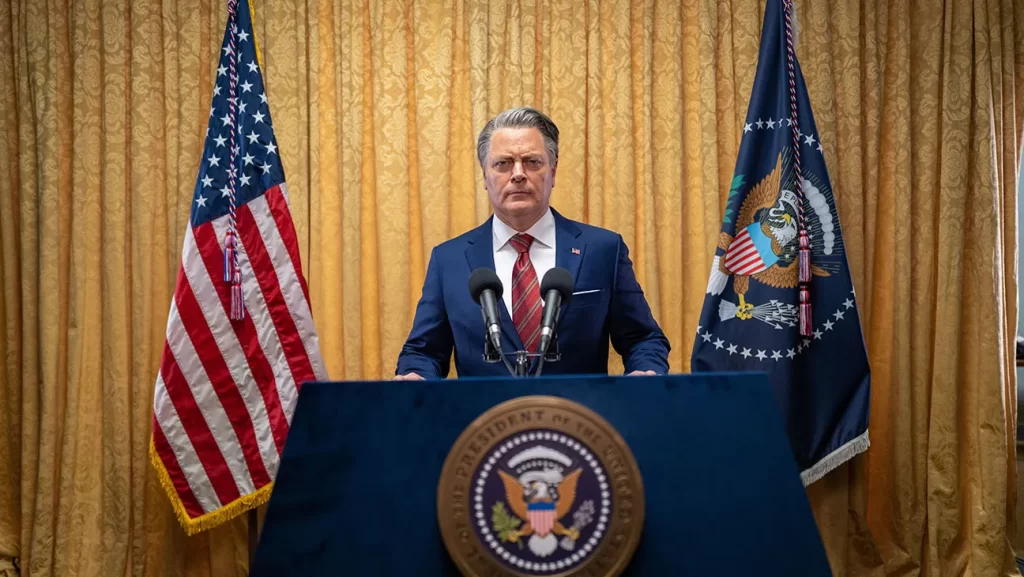

Owen lives a sheltered existence with his overprotective parents (played by Danielle Deadwyler and an exceptionally creepy Fred Durst). His father exerts a tight grip on the household, shunning Owen for his unconventional interests. Owen needs an escape, and he eventually finds it through a television set.

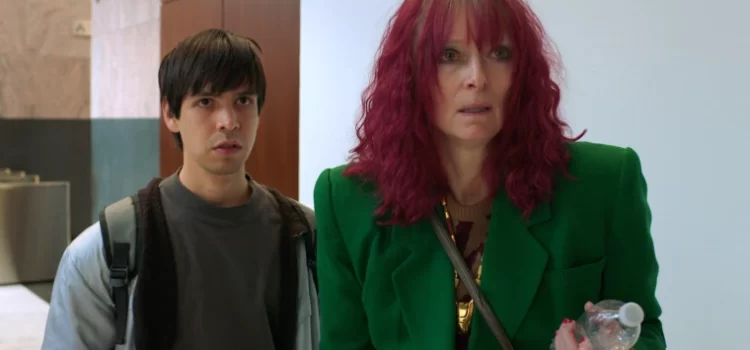

One evening, while wandering around his local high school (fittingly called “Void High”) waiting for his mother to cast a ballot for a local election, Owen finds ninth-grader Maddy (Brigette Lundy-Paine) reading an episode guide for a TV show called “The Pink Opaque.”

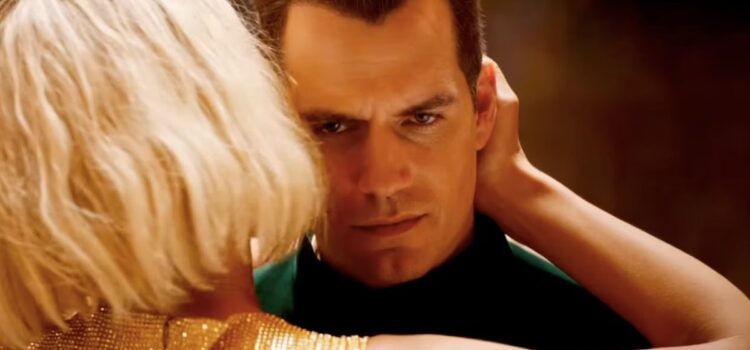

The supernatural serial is an homage to “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and features two girls, Tara and Isabel, who communicate via the astral plane. They fight various “monsters of the week,” with the all-powerful Mr. Melancholy pulling the strings and watching over them as a garish face on the moon.

Maddy — wry, severe, and enduring a troubled home life— quickly strikes up a friendship with Owen, and Owen sneaks over to Maddy’s house for a sleepover to watch the show: he’s hooked. Maddy and Owen find “The Pink Opaque” to be an escape from reality: they’re outcasts who connect to the characters’ isolation, confusion, and eventual empowerment. They’re both stuck in a limbo that’s suffocating their developing minds and bodies, only finding solace via their heroes on the other side of the screen.

Flash forward two years, and Owen continues to use “The Pink Opaque” as a way to cope with his trauma and gradually develop his sense of self, with Maddy leaving VHS recordings of each episode in Void High’s darkroom for him to take home.

Owen and Maddy’s obsession with the show grows, tragedy strikes, and the lines between reality and fantasy blur to increasingly psychedelic effect, as “The Pink Opaque” bleeds off the screen into Owen’s lived experience. He grapples with his true identity amid the weight of suffocating societal pressures and the rapid passage of time.

Indeed, “I Saw the TV Glow” is a disturbing and bleakly existential watch. Schoenbrun, in their second feature film, has a distinctive cinematic voice – presenting a story that’s both easy to become invested in and difficult to fully parse, evoking familiar themes in ways that prove constantly surprising, unsettling, and, at times, bewildering.

It’s a film that refuses to explain itself and leaves the door open to different interpretations, particularly during its head-spinning conclusion. This is an obviously personal story for Schoenbraun, one that’s rendered in an uncompromising, polarizing style that says as much through its mood-setting as through dialogue.

Their approach allows us to feel what the characters are feeling as they drift through their nebulous environment, even as they themselves are unsure how to process what’s going on.

“I Saw the TV Glow,” in its patient, Lynchian rhythms, establishes a palpable sense of dread from its opening moments, as Schoenbrun and cinematographer Eric K. Yue thrust us into a wasteland where a sense of dreariness practically leaks off the screen – a dark, neon-infused, almost alien world that Owen and Maddy inhabit as outsiders unsure of life’s meaning.

Schoenbrun twists seemingly inviting spaces into symbols of malaise and menace despite their seeming banality, further emphasizing Owen’s alienation and perceived sense of “otherness.” This world represents an abyss that’s willing to swallow Owen and Maddy whole if they don’t fight to break free from its spell.

The Pink Opaque, too – depicted in authentic detail with title cards, music, acting, and lo-fi effects from the era –- is both alluring and sinister. Owen and Maddy form a connection to another world that’s dictated by the whims of showrunners and networks; a dangerous reliance on an external source to find comfort in a place that’s all too willing to take it away.

Suffice to say, “I Saw the TV Glow” is quite a depressing watch, interspersed with moments of dry humor and supernatural imagery that may or may not be taking place in traditional “reality.”

We’re seeing the world through Owen’s eyes – portrayed by Foreman and Smith with a haunted melancholy giving way to mounting existential panic – and his truth is yearning to be embraced; the question is, will he realize it before his depression and dysphoria consume him?

As the film progresses down its increasingly head-spinning path, “I Saw the TV Glow” maintains a grim momentum, as Owen wages an internal battle against prejudiced norms and his seeming lack of agency.

The evocative, thematically resonant soundtrack enhances the proceedings, furthering the sense that Owen and Maddy are living in a dream, and years swiftly pass while his conflict stays the same, visualized in sterling makeup work.

The real horror of “I Saw the TV Glow” is a battle of identity, of being reliant on technology and consumable entertainment for discovering who we are, rather than forging one’s own path in a dark, depressing world.

It’s a relevant message, if not an especially uplifting one – easy to connect to regardless of background. Owen’s, and Schoenbrun’s, stories may be unique to them, but few films in recent memory are as unsettling, poignant, or conversation-starting as “I Saw the TV Glow.” Whether or not you can get on board with its story and style, it’s an experience that won’t be easily forgotten.

“I Saw the TV Glow” is a 2024 horror-drama directed by Jane Schoenbrun and starring Ian Foreman, Justice Smith, Bigette Lundy-Paine, Danielle Deadwyler and Fred Durst. It is rated PG-13 for violent content, some sexual material, thematic elements and teen smoking and runtime is 1 hour, 40 minutes. It opened in theaters May 17. Became available Video on Demand on June 14 and DVD on July 30. Alex’s Grade: A.

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.