By Lynn Venhaus

Marked by twists, turns and a “Twilight Zone” flair, Albion Theatre Company’s latest whip-smart production “I Have Been Here Before” ponders the construct of time in a shrewd yet abstract way.

An adroit ensemble of six piques our curiosity, each one developing layers of their characters’ personalities and motivations. They seamlessly embody different classes, all at crossroads (whether they realize it or not).

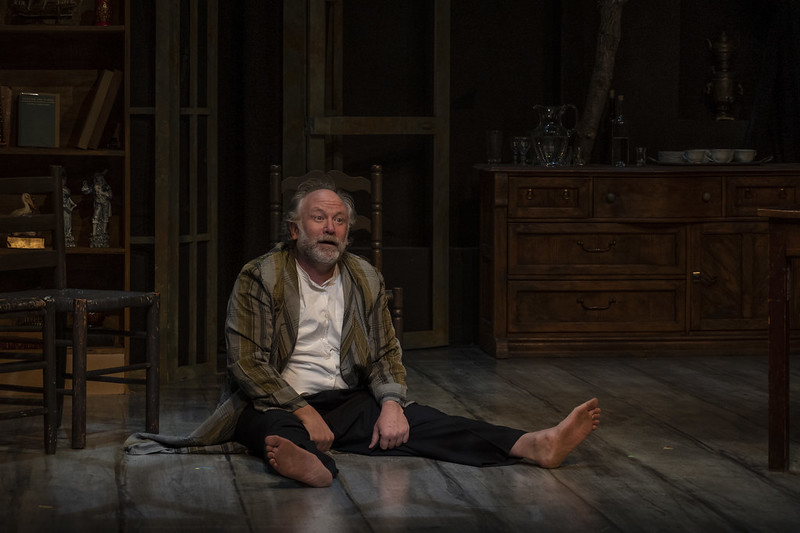

The Black Bull Inn in Grindle Moor, part of the remote Yorkshire countryside, is where the story takes place in 1937. Set designer Rachel St. Pierre has fashioned a cozy, modest parlor, with Brad Slavik the astute set builder and Gwynneth Rausch specific in appropriate time-period props.

They have effectively set the period and place, so that co-directors Robert Ashton and C.J. Langdon were able to keep the characters on the move, so they weren’t as stodgy as they probably were nearly 90 years ago.

The six accomplished performers were notably well-rehearsed with distinct dialects and physically nimble in their mannerisms, driving the story with more verve than playwright J.B. Priestley’s dated drama indicated.

Today, the show hasn’t aged as well or is as suspenseful as an Alfred Hitchcock classic or even an Agatha Christie drawing room mystery. The set-up in the first act is intricate and lengthy, then has more engaging action in second act, while the third act teeters on implausible. Nevertheless, the sheer will and the skills of the actors make this watchable.

Priestley continued his fascination with theories of time here; one of the 39 he wrote. “Time and the Conways” and “Dangerous Corner” were among his most successful plays about time – he wrote seven.

He believed different dimensions could link past, present and future, and philosophizes, using Russian teacher P.D. Oupensky’s theory of eternal recurrence, which are life circles or spirals.

Robert Ashton and Anna Langdon are the reliable Sam Shipley and Sally Pratt, father and daughter innkeepers. He’s amiable, she’s pragmatic in their portraits. They are expecting three guests while a quiet but agreeable young headmaster, Oliver Farrant (Dustin Petrillo), is already spending a vacation there, for a rest. He relaxes by reading and going for long walks.

The upcoming holiday is known as Whitsuntide, around the time of the Christian holy day the Pentecost. In the south of England, it was the first official holiday of the summer (until replaced in 1971).

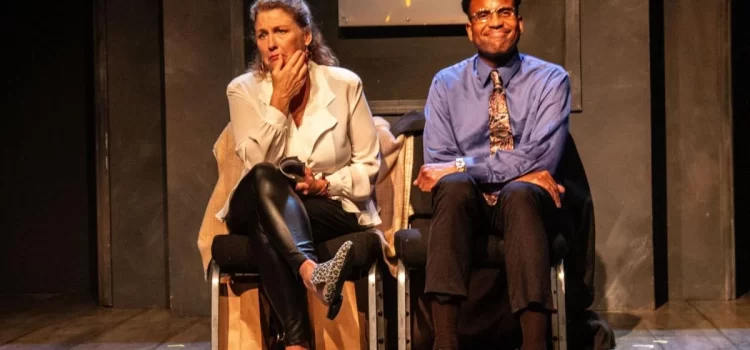

But the guests that reserved the rooms have cancelled. That allows a foreign guest, professor Dr. Gortler, (Garrett Bergfeld) and a wealthy businessman and his stylish wife, Walter and Janet Ormund (Jeff Kargus and Bryn McLaughlin), to book separate rooms.

Tall, gruff and exiled from Nazi Germany, the mysterious professor has already startled Sally by practically predicting future outcomes. He seemed to know who would be staying and not who originally booked rooms.

Are they thrown together by chance or is it on purpose? That is one of the many questions raised as the plot thickens. It is rather odd that somehow, they seem inter-connected. Their decisions could have consequences that would affect others.

There is a nagging feeling that they may have lived through this experience before. But how could that be? The cosmic undertones seem to rattle some cages, especially suspicious Sally.

An expert in math and science, Gortler is blunt at asking perceptive questions, revealing predictions, and shares a precognitive dream describing preposterous occurrences between everybody there. Dun dun dunnn!

Quite surprising is an assured, imposing performance by Garrett Bergfeld as the enigmatic professor. It’s been 20 years since he stepped on a stage, and one hopes it will continue.

Dustin Petrillo, who is always authentic in his portrayals, displays emotional depth and an unmistakable connection with Mrs. Ormund, who is unhappy with her workaholic – and alcoholic – husband.

Petrillo and Bryn McLaughlin worked together beautifully as husband and wife in “The Immigrant” at New Jewish Theatre two years ago, and they smoothly convey an ease with each other.

As restless Janet, McLaughlin contrasts her comfort with Farrant by showing unease with her inattentive husband.

Jeff Kargus is striking as the swaggering Ormund, used to getting what he wants and believably upper crust in speech and movement. He commands the stage, appearing as a manipulative mover and shaker, giving off shady vibes. One wanted to know more about these puzzling people.

As impressive as the actors are, so is the creative team that collaborated on a well-worn look, including the aforementioned scenic/prop designers. Costume designer Tracey Newcomb, whose work is always memorable, has economically created status in her ideal apparel choices. Lighting designer Eric Wennlund and sound designer Leonard Marshell set the mood well.

In 1970, rock group Crosby Stills Nash and Young released an album, “Déjà vu,” including a song of the same name.

If I had ever been here before

I would probably know just what to do

Don’t you?

If I had ever been here before on another time around the wheel

I would probably know just how to deal

With all of you

It later ends with the lyric, “We have all been here before” repeated several times. (“It’s déjà vu all over again,” in the words of an epic St. Louis philosopher-raconteur Yogi Berra.)

I was frequently reminded of those lyrics, as the play attempted to explain unnatural phenomenon. Had it followed through with a more convincing ending, it would have stuck the landing, but this is an observation in hindsight 90 years later.

Priestley worked with what was known at the time, and his own viewpoint on another life ahead as a do-over. Food for thought, to be sure.

In their customary fine fashion, Albion presented an unfamiliar play effectively, driven by excellent performances and strong contributions by local artisans.

Albion Theatre presents “I Have Been Here Before” Thursday through Saturday at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 2 p.m., on Oct. 23-26, 30-31; Nov. 1-2 at the Black Box Theatre at the Kranzberg Center, 501 N. Grand in Grand Center. The show runs 2 hours, 30 minutes, with two 10-minute intermissions. For more information: albiontheatrestl.org.

Lynn (Zipfel) Venhaus has had a continuous byline in St. Louis metro region publications since 1978. She writes features and news for Belleville News-Democrat and contributes to St. Louis magazine and other publications.

She is a Rotten Tomatoes-approved film critic, currently reviews films for Webster-Kirkwood Times and KTRS Radio, covers entertainment for PopLifeSTL.com and co-hosts podcast PopLifeSTL.com…Presents.

She is a member of Critics Choice Association, where she serves on the women’s and marketing committees; Alliance of Women Film Journalists; and on the board of the St. Louis Film Critics Association. She is a founding and board member of the St. Louis Theater Circle.

She is retired from teaching journalism/media as an adjunct college instructor.