By CB Adams

The holiday zeitgeist feels different this year. Maybe it’s because we need some relief from the unrelenting news cycles filled with war, strife and discord. Or maybe we’re still emerging – chrysalis-like – from the lingering fog of the COVID pandemic. Or maybe it’s due to that fabulously fun new Christmas album that Cher just dropped.

No matter the reason, the feeling in the air is that “…we need a little music, need a little laughter / need a little singing ringing through the rafter / and we need a little snappy, happy ever after,” to quote Jerry Herman’s “We Need A Little Christmas.” Delivering more than “a little” Christmas is Cirque Du Soleil’s supersized, supercharged and super-athletic “’Twas the Night Before…,” running at the Fabulous Fox through December 10.

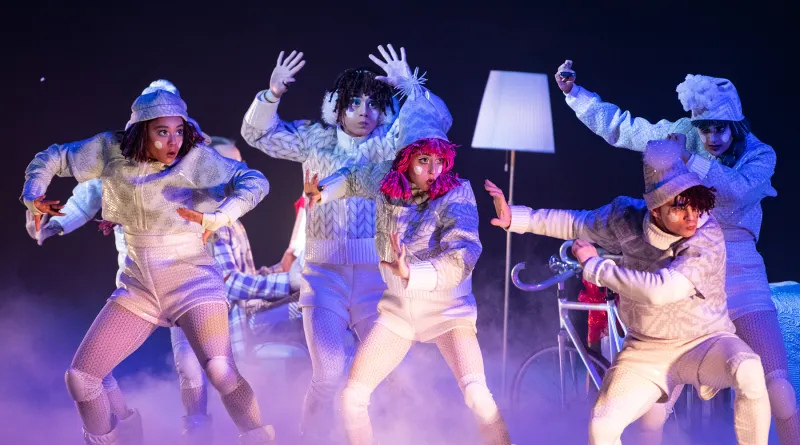

“Twas the Night Before…,” which debuted several years ago, is the first holiday show – make that spectacle – by Cirque du Soleil. It’s loosely based on Clement Clarke Moore’s chestnut, “A Visit from Saint Nicholas.” The show follows the poem’s storyline using Cirque’s creative interpretation of circus arts – aerobatics, gymnastics, tumbling, juggling, diabolo yo-yos, clown bike and the like. Of course, Cirque being Cirque (under the direction of senior artistic director, James Hadley), the show envelopes the performers with over-the-top staging that includes a stunning amount of tinsel, props and fake snow that creates an immersive, richly saturated experience.

The show’s recorded soundtrack is equally creative and pulse-pounding without being overwhelming. According to Jean-Phi Goncalves, the show’s musical composer, “My goal in creating this music was to introduce a little holiday surprise in every track. By taking the essence of these Christmas classics…and adding a modern twist with electronics, big drums and fat basses, we were able to reveal them in a completely new light. I like to think that the reconstructed pieces speak to Christmas music lovers as well as those who have yet to embrace the genre.”

The percussive soundtrack achieves all that – and more. It’s a major contributor to the propulsive nature of “Twas the Night Before…” The show is one the “fastest” ways to spent 90 minutes as it presents Cirque’s story about a jaded young girl who rediscovers the magic of the holidays.

The spectacular staging, lighting design (some of quite high-tech), shimmering costumes and music all serve the acrobatic athleticism of the performers.

Adorability-wise, the reindeer are the hands-down winners. In golden jockey costumes with satiny underbellies, they have their names emblazoned on their backs. Diving through hoops at increasing heights, they’re comical and impressive — and it’s charming somehow that Prancer (Jinge Wang), never the starriest member of Santa’s team, is the best of all.

“A Visit From St. Nicholas,” introduced the world to Santa’s reindeers. You know, Dasher, Dancer, Prancer and the rest of the team? “Twas the Night Before…” transforms the reindeers into comic characters with jockey-inspired golden costumes and mannerisms like jockeys. Their big number, which involves diving through ever-higher hoops, occurs near the climax of the show.

There are no weak acts in this show, whether it’s the opening aerial pas de deux with two male performers, the tumbling antics of a bunch of mice or a mash up of ballet and contortion within a hotel cart. There’s even a roller disco act that is so good that it’s easy to forget to question what it has to do with the story.

“’Twas the Night Before…” is advertised as something for the whole family. Usually when I see that phrase, it means that it dumbs-down things to a child’s level. Not so with this show. Everyone, from the kiddos to their elders, can become enchanted by the performance. It’s diverting in all the best ways and delivers a big little Christmas, “right this very minute.”

“’Twas the Night Before…” at The Fabulous Fox runs through Dec.10. For tickets and information go to The Fabulous Fox website.

CB Adams is an award-winning fiction writer and photographer based in the Greater St. Louis area. A former music/arts editor and feature writer for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, his non-fiction has been published in local, regional and national publications. His literary short stories have been published in more than a dozen literary journals and his fine art photography has been exhibited in more than 40 galley shows nationwide. Adams is the recipient of the Missouri Arts Council’s highest writing awards: the Writers’ Biennial and Missouri Writing!. The Riverfront Times named him, “St. Louis’ Most Under-Appreciated Writer” in 1996.