By CB Adams

Set in Harlem’s iconic Sugar Hill—once home to luminaries like W.E.B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall and Duke Ellington—”This House,” the new, commissioned opera by composer Ricky Ian Gordon and librettists Lynn Nottage and her daughter, Ruby Aiyo Gerber, arrives at Opera Theatre of St. Louis with sweeping ambition and a world-premiere spotlight.

Its strengths lie in OTSL’s commitment to new works, a fully committed cast, inventive staging and design, and evocative playing by members of the St. Louis Symphony under the direction of principal conductor Daniela Candillari.

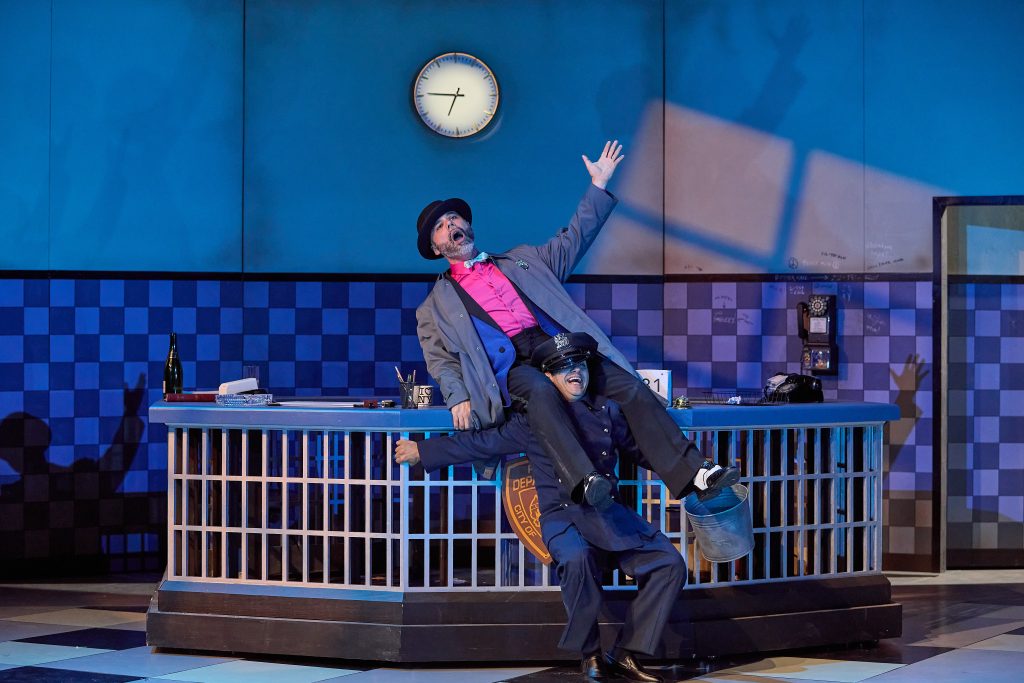

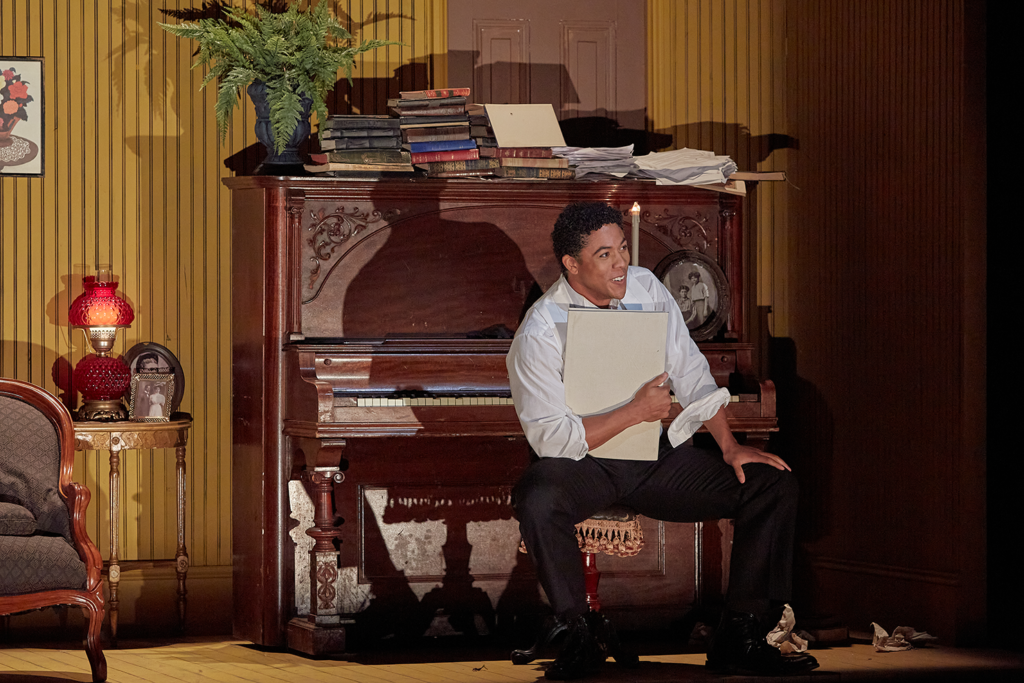

The production, directed by James Robinson, features a fine ensemble led by soprano Adrienne Danrich as matriarch Ida and mezzo-soprano Briana Hunter as her daughter Zoe. Baritone Justin Austin brings supple emotional nuance to the role of Lindon, Ida’s son, while Christian Pursell lends warmth and pathos to Thomas, Lindon’s lover.

Tenor Brad Bickhardt portrays Zoe’s husband Glenn, and bass Sankara Harouna takes on the role of Ida’s husband, Milton. The cast is rounded out by soprano Aundi Marie Moore, tenor Victor Ryan Robertson, soprano Brandie Inez Sutton, and mezzo-soprano Krysty Swann.

One of the most compelling presences in the opera is the Walker family’s brownstone itself—less a backdrop than a central character. Over more than a century, it bears witness to couplings, births, betrayals, addiction, activism and grief – among a litany of other human experiences .

It is a house imbued with memory, both sacred and unsettling—a place that might, in real-estate parlance, be labeled a stigmatized property or psychologically impacted. But in family gossip, media headlines or the real talk of buyers and agents, this would be known bluntly as a murder house. And it’s precisely this fraught legacy—how spaces carry the spectral weight of history—that “This House” tries to explore, if not fully resolve.

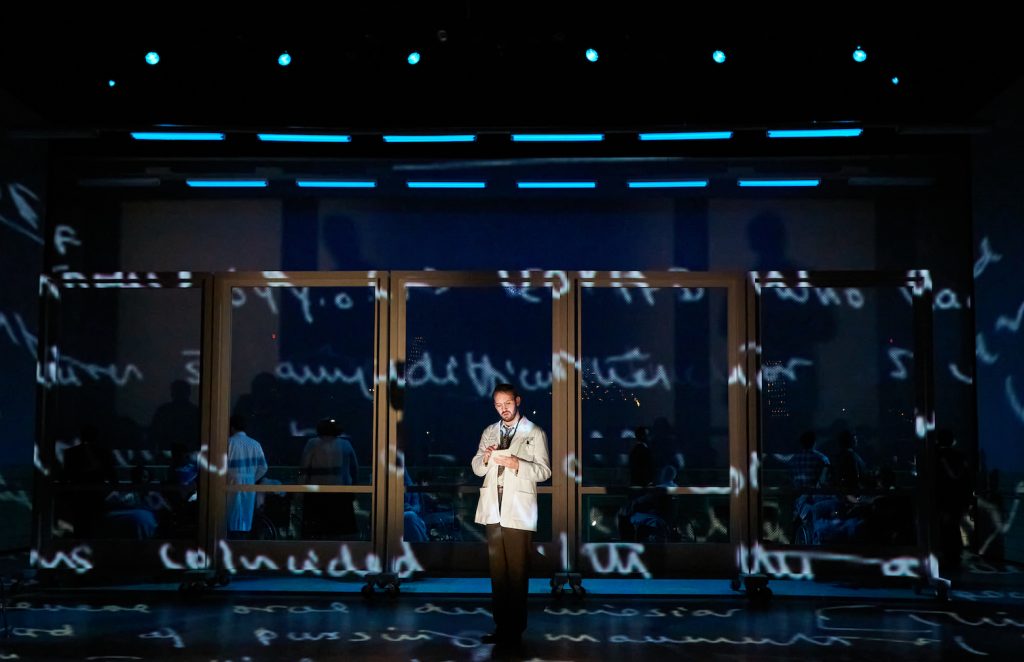

Composer Ricky Ian Gordon underscores the house’s haunting role by assigning the orchestra’s reed section an eerie vocalise, a ghostly exhale that recurs like a memory trying to resurface. Scenic designer Allen Moyer, video designer Greg Emetaz and lighting designer Marcus Doshi create a visually rich, immersive world that roots the opera’s fragmented narrative in emotional atmosphere.

Moyer, known for “Grey Gardens” and his longtime collaboration with Gordon (“The Grapes of Wrath”), outfits the home with dignified wear and subtle detail—its furnishings shifting over time like the emotional residue of those who’ve passed through. The use of a carousel to move from interior and exterior scenes was as effective as it was impressive.

Emetaz’s excellent cinematic projections add a lyrical visual language that binds characters to time and place. Doshi’s lighting moves seamlessly across eras, illuminating past wounds and present tensions with emotional fluency. And Tony-winning costume designer Montana Levi Blanco’s work grounds the characters with clarity and texture, often accomplishing through wardrobe what the script cannot.

Director Robinson guides the sprawling libretto with attention to pacing and emotional clarity, though the sheer number of narrative threads makes cohesion elusive. The staging is precise, yet the storytelling remains episodic, moving from decade to decade with little connective tissue other than the house itself and the family’s lineage.

The house, for all its beautifully rendered symbolism, ends up standing in for a history that the libretto doesn’t fully explore—a repository of vignetted trauma, legacy and memory that’s often gestured toward rather than meaningfully unpacked.

The cast delivers deeply felt performances that do the best they can to elevate the material. Hunter’s Zoe, a frustrated millennial searching for answers, brings grit and lyrical finesse to a role that could easily feel schematic. Danrich’s Ida exudes quiet strength and vulnerability, her soprano capturing the tension of survival and sorrow.

Austin and Pursell form the opera’s emotional core with understated yet resonant chemistry. Victor Ryan Robertson’s Uncle Percy resonates with presence, embodying the lingering complexities of family and memory.

Yet despite these achievements, “This House” buckles under the weight of too many competing ideas. Gentrification, addiction, queer identity, generational trauma, cultural legacy—each theme has potential, but none are given enough narrative space to mature.

Characters appear, hint at depth and vanish. Even moments of violence—presumably pivotal—are staged with such abruptness that their emotional impact feels blunted. In this way, the opera mirrors its title too well: a house with many rooms, stories left half-told behind closed doors.

The creative pedigree behind the work raises the stakes. Nottage, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner in playwriting, is known for emotionally rich, structurally disciplined writing. Gordon, celebrated for his genre-fluid scores and nuanced theatrical sensibility, draws here from a wide palette: ragtime, jazz, gospel, and more.

His ambition is to “place words like a jewel in a ring.” But too often, the music recedes into the background, more atmospheric than dramaturgical. The score supports rather than shapes the action, and its emotional cues—while sometimes lovely—rarely surprise or challenge.

There are glimpses of brilliance: a melodic motif that pierces, a costume that reveals a character’s arc, a lighting shift that clarifies a ghost’s presence. But the opera’s structure—sprawling and impressionistic—ultimately dilutes its impact. If that was a deliberate choice – and presumably it is – its effect does not satisfy.

In real estate, buyers might walk into a home like the Walkers’ and wonder: Who lived here? What happened in these rooms? “This House” the opera wants to address these questions—the idea that buildings remember—but it gets lost in the hallways. Despite noble intentions and undeniable talent, the result feels less like a unified meditation on lineage and place and more like a haunted, curated scrapbook of ideas—rich in atmosphere, scattered in focus and ultimately more whispered promise than resonant legacy.

Opera Theatre of St. Louis’ production of “This House” continues in repertory at the Loretto-Hilton Center of Performing Arts at Webster University through June 29. For more information, visit https://opera-stl.org.

CB Adams is an award-winning fiction writer and photographer based in the Greater St. Louis area. A former music/arts editor and feature writer for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, his non-fiction has been published in local, regional and national publications. His literary short stories have been published in more than a dozen literary journals and his fine art photography has been exhibited in more than 40 galley shows nationwide. Adams is the recipient of the Missouri Arts Council’s highest writing awards: the Writers’ Biennial and Missouri Writing!. The Riverfront Times named him, “St. Louis’ Most Under-Appreciated Writer” in 1996.