By Alex McPherson

Overflowing with self-importance that threatens to drown out its several competent elements, director Mike Flanagan’s “The Life of Chuck” is neither as profound nor as poignant as it thinks it is — a film so carefully-composed that genuine, earned emotion is ultimately left as an afterthought.

Based on the Steven King novella of the same name, Flanagan’s latest begins with the horror-inflected Act 3: the end of the universe as we know it. Chunks of California are breaking off into the ocean, Florida is underwater, fires engulf the Midwest, and the Internet is out. Posters and advertisements are plastered everywhere thanking a sharply-dressed Chuck Krantz (Tom Hiddleston) for “39 great years!” Nobody has a clue who Chuck is.

We follow Marty Anderson (a typically soulful Chiwetel Ejiofor), a devoted but increasingly exhausted middle school social studies teacher and fan of Carl Sagan. Marty is a cool-headed, empathetic person unwilling to accept that it’s the actual “end of the world.”

At parent-teacher conferences — as attendance continues to decline in school — he helps console anxious parents who aren’t sure what to do amid it all; one of them (David Dastmalchian) bemoans the loss of PornHub. Humanity, more generally, seems to be on a slow walk towards Armageddon, with the majority resigned to their fate.

Marty reconnects with his ex-wife, Felicia Gordon (Karen Gillan), an overworked ER nurse whose department has become known as “The Suicide Squad.” Marty and Felicia see a last chance to bond before the universe is snuffed out; not even Marty’s hopeful view of Sagan’s cosmic calendar can dissuade him from preparing for The End.

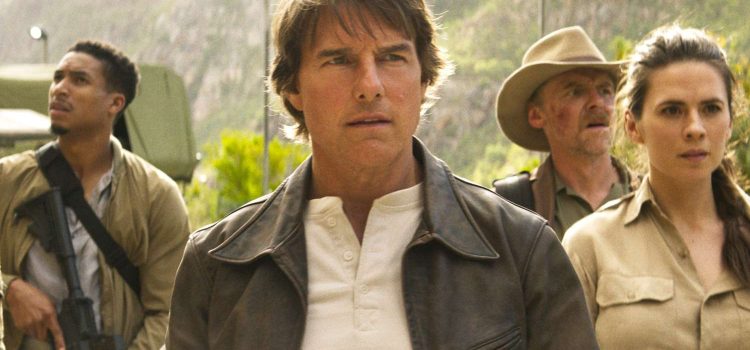

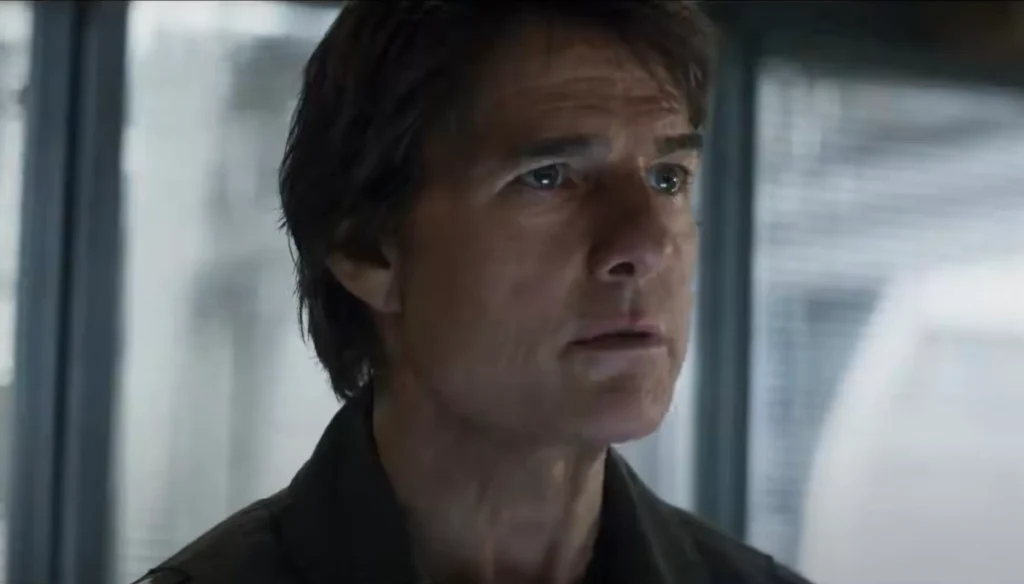

Jump to Act 2. Adult Chuck is a jaded accountant on a business trip in downtown Boston. While walking down a bustling street, Chuck sees a talented but underappreciated busker (real-life drummer Taylor Gordon a.k.a. The Pocket Queen) and gets to dancing — Chuck has quite the moves.

A crowd gathers to watch and gawk at Chuck/Hiddleston, including Janice (Annalise Basso), a woman whose boyfriend broke up with her moments earlier through text. She starts dancing with Chuck, and, for a brief time, they’re both able to escape their demons and live in the moment.

Afterwards, Chuck looks wistfully off into the distance, reminiscing about his life and, as narration from Nick Offerman reminds us, his fleeting remaining time alive.

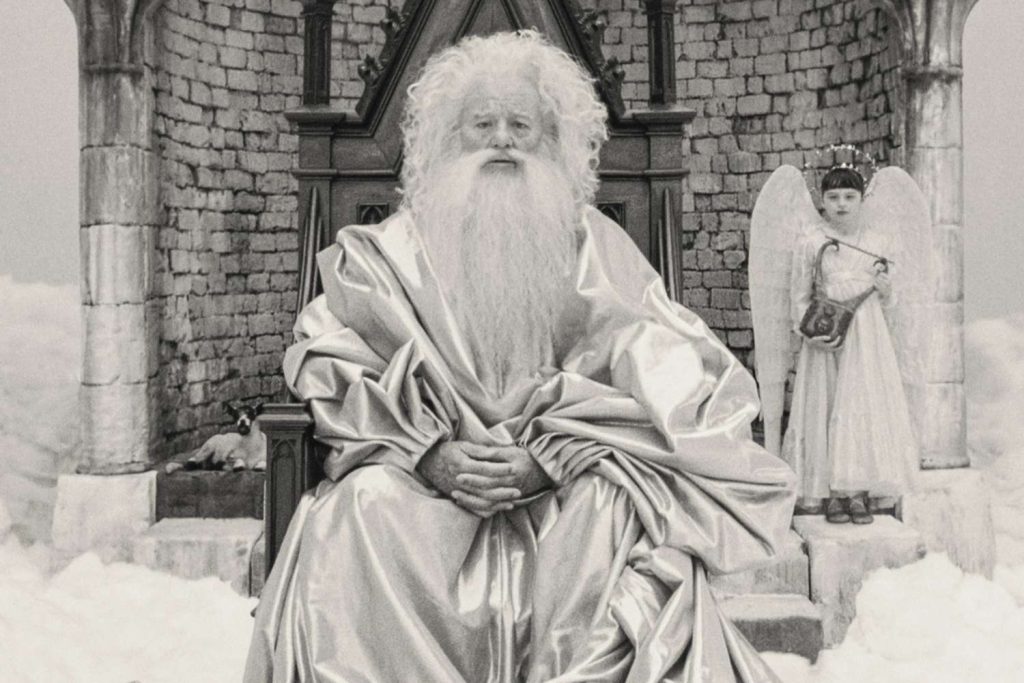

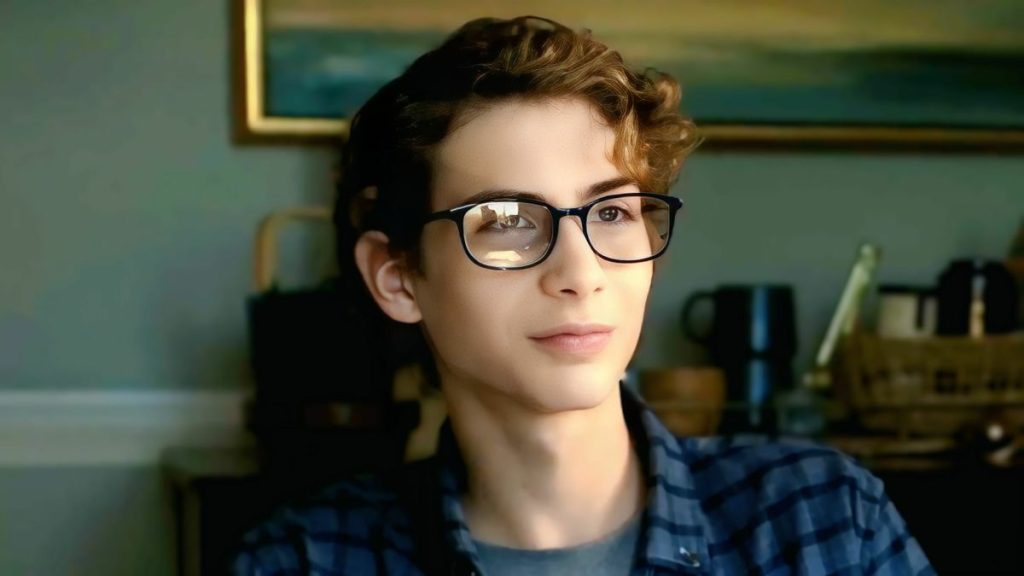

Act 1 takes us back to Chuck’s childhood — he’s portrayed by Cody Flanagan, Benjamin Pajak, and Jacob Tremblay. Chuck experiences family tragedy and life’s ups-and-downs with his grandparents Albie and Sarah (Mia Sara and Mark Hamill).

He also discovers his love of dance while grappling with a rushed transition into adulthood, becoming fascinated with the strange “ghost” in the locked room upstairs that deeply frightens Albie.

Needless to say, there’s a lot going on in these three chapters, but, at the same, there’s not much to chew on. Individual scenes and performances break through the prevailing schmaltz, but for a story ostensibly about the importance of spontaneity and of living in the moment, “The Life of Chuck” paints a canvas both messy and overwrought, remaining thoroughly full of itself from start to finish. Several characters like to spout a phrase coined by Walt Whitman: “I contain multitudes” — the same, it must be noted, does not apply to this film.

It starts off strongly enough, though. Flanagan’s roots as a horror director shine through in Act 3 — establishing an eerie tone from the get-go with darkly comedic dialogue and an atmosphere of existential malaise and hopelessness. It’s a bit hokey, sure, but intriguing, with its end-of-the-world happenings not seeming all that implausible.

The conclusion is surprisingly dark, too, especially given distributor Neon’s saccharine marketing campaign. Flanagan’s directing is precise, carefully-composed, and efficient, knowing how to play us for sudden jolts of fear and bursts of unexpected (R-rated) humor.

There’s also real truth to how “The Life of Chuck” depicts humanity’s fatigue and fatalism given today’s horrors off-screen. If only the film committed more to the mystery: Acts 1 and 2 excise most of the story’s compellingly dark and off-kilter threads to embrace sentimentality and ponderous storytelling.

Indeed, much like Chuck and Janice’s exuberant dancing — which Flanagan and cinematographer Eben Bolter present with toe-tapping, quick-cut pizazz — the rest of “The Life of Chuck” feels too precious, too precisely-tailored to tug at the heart strings, and oddly-structured, content to explain rather than let viewers put the pieces together themselves.

And, in the end, “The Life of Chuck” is far from revelatory in its views on “the universe contained within us all,” leaning into directorial showmanship to conventional ends.

Hallmark-card-worthy sentiments are rendered in faux-Spielbergian fashion, with hints of supernatural suspense, supported by a warmly inspirational score from The Newton Brothers and an ensemble that breathes warmth, if not necessarily depth, to characters slotting into Flanagan’s film like cogs in a well-oiled machine.

Narration from Nick Offerman — presumably reading direct passages of King’s text — interrupts scenes to explain characters’ thoughts and navigate the story’s various time jumps. While this choice helps create a storybook feel, it’s limiting, given the story’s segmented structure (focusing on “big moments” in Chuck’s life).

Nuance is swapped for clarity and brevity — cutting out seemingly crucial connective tissue between Acts 1 and 2 — plus a near-worshipping of King’s source material: a short story expanded to feature length.

Hiddleston is great as usual, albeit not given all that much screen time, adding a sense of mournful reflection to Chuck’s later years as he’s made aware of the small joys in life once again. The younger actors portraying Chuck in Act 1 effectively convey both Chuck’s youthful naivete and gradual coming-of-age.

Sara and Hamill give the film’s most convincing, lived-in performances, with Hamill in particular getting the chance to engage in some Oscar-friendly speechifying, as the alcoholic, superstitious Albie counters young Chuck’s idealism around dance/the arts with a more pragmatic view on what lies ahead.

This excellent ensemble — including other notable turns from Matthew Lillard, Carl Lumbly, and Samantha Sloyan — coupled with Flanagan’s meticulous style of framing and sharp (but not organic) dialogue boosts the film above mediocrity. So long as one doesn’t think too hard about its existential musings, “The Life of Chuck” goes down easy enough.

But despite a compellingly unusual beginning and a handful of well-crafted sequences scattered throughout, it never fully takes flight. At the end of the day, it’s all trying too hard: irritatingly manufactured and only fitfully involving.

“The Life of Chuck” is a 2024 science fiction-fantasy-drama directed by Mike Flanagan and starring Tom Hiddleston, Mark Hamill, Mia Sara, Benjamin Pasak, Jacob Tremblay, Cody Flanagan, Karen Gillan, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Matthew Lillard. Its run time is 1 hour, 51 minutes, and it is rated R for language. It opened in theatres June 6. Alex’s Grade: C+.

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.