By C.B. Adams

I hold it true, whate’er befall;

I feel it, when I sorrow most;

‘Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.

– “In Memoriam:27”, Alfred Lord Tennyson

To key off Tennyson’s philosophical proposition, Opera Theatre of St. Louis’s “Awakenings,” at the Loretto-Hilton Center’s Virginia Jackson Browning Theatre through June 25, explores a similar notion. If you were a patient trapped for decades by encephalitis lethargica , spending your waking moments in constant stupor and inertia, would you agree to allow a doctor like the neurologist Oliver Sacks to experimentally administer a drug called levodopa, or L Dopa, that could alleviate the disease’s debilitating effects? And, would you consent if you knew the risks – that the effects might not last long and that you would still suffer, like a sort of Rip Van Winkle, from spending decades isolated from the world’s events and your own maturity and development?

Is it better, then, to have been awakened than not at all?

That’s a powerful philosophical question dreamed up in Sack’s book “Awakenings” that presented a series of fascinating case reports of patients trapped by encephalitis lethargica. It was also dreamed up into the eponymous Hollywood film (starring Robert DeNiro and Robin Williams), a documentary, a ballet and a play by Harold Pinter. Sacks himself dreamed it could even be this opera, a pandemic delayed premiere by OTSL this season.

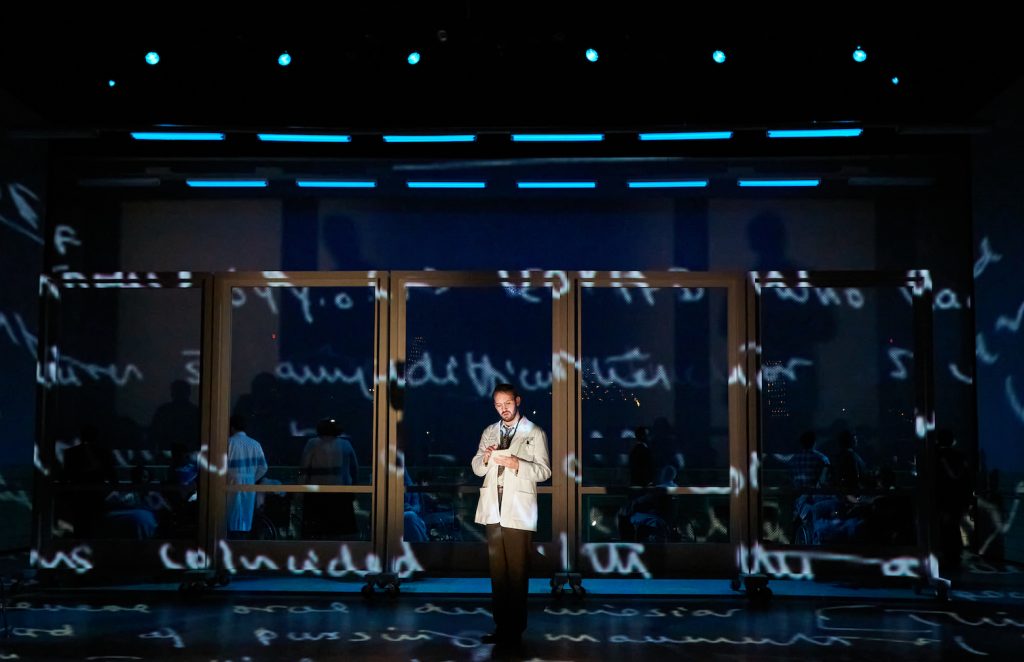

This production draws the audience into the clinical but dreamlike world even before the score begins. The opening set evokes an impersonal, sterile hospital setting as nurses slowly wheel in slumped patients behind a series of moveable glass walls. Though not “pretty,” the harsh, set design by Allen Moyer is visually affecting and well-matched to the opera’s melancholic intensity (including a fantastic use of video projections by Greg Emetaz), especially as illuminated by Christoper Akerlind’s lighting designs.

The “Awakenings” score, performed by the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Robert Kalb, is excellent if not exactly memorable. The music weaves around the characters and action without calling attention to itself.

Baritone Jarrett Porter sings Dr. Sacks, and his rich voice is well-matched to the demands of the role as a deeply empathetic caregiver. Porter’s voice is well-matched to the bass-baritone of David Pittsinger, who voices Sacks’s naysaying boss, Dr. Podsnap. Pittsinger’s presence and deep voice provide believable authority.

One of the key reasons “Awakenings” shines is the opera’s balancing of multiple “awakenings” by Sacks, who grapples with his sexuality in a subplot, as well as three patients that representing the 20 in real life. They provide more than yeoman’s work as they must sit in wheelchairs – all trembles and contortions – and then transform into walking/talking human beings then return to their un-awakened states.

Marc Molomot, tenor, plays a middle-aged Leonard, whose aging mother (sung beautifully and dutifully by Katherine Goeldner) has been reading to him every day since he succumbed to his condition. Molomot confidently provides a Leonard who hasn’t emotionally matured since adolescence. He’s a boy in a man’s body, which makes life exciting, challenging and ultimately disturbing. Molomot plays Leonard with aplomb.

One of the highlights of “Awakenings” is Leonard’s duet with Rodriguez, his male nurse, sung by the tenor Andres Acosta. Acosta proves there are no parts too small to stand out.

Another of the trio of patients is Rose, engagingly sung by Susannah Phillips. Rose is an optimistic yet dreamy character, still living in an interrupted past that includes a long-gone love. Phillips’s performance and engaging voice make it easy to start identifying with her fairytale outlook and then mourn as she returns to her former state.

Completing the trio is Miriam H, sung by soprano Adrienne Danrich. Miriam’s story is as unique and ultimately tragic as her cohorts. Like Rose, Miriam’s story moves from silence to astonishment as she discovers that her family considered her dead and that she has a daughter and even granddaughter. Danrich’s performance and beautiful voice elevate the tragedy of her return to silence.

As directed by James Robinson, “Awakenings” is a compelling experience – one that calls to mind Bob Dylan’s Series of Dreams: “…Thinking of a series of dreams / Where the time and the tempo drag, / And there’s no exit in any direction…”

Long after the performances fade, the philosophical and ethical questions posed by “Awakenings” linger. Would have the lives of Mirian, Rose and Leonard (and perhaps even Sacks himself) have been better if they hadn’t been intervened by L Dopa? And who should be allowed to make that choice? One person’s dream may be another’s nightmare.

CB Adams is an award-winning fiction writer and photographer based in the Greater St. Louis area. A former music/arts editor and feature writer for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, his non-fiction has been published in local, regional and national publications. His literary short stories have been published in more than a dozen literary journals and his fine art photography has been exhibited in more than 40 galley shows nationwide. Adams is the recipient of the Missouri Arts Council’s highest writing awards: the Writers’ Biennial and Missouri Writing!. The Riverfront Times named him, “St. Louis’ Most Under-Appreciated Writer” in 1996.