An action extravaganza delivering unforgettable set pieces while adding more layers to its damaged protagonist, director Chad Stahelski’s “John Wick: Chapter 4” is a masterclass in balletic bloodletting that rivals the likes of “The Raid: Redemption.”

Continuing the story from 2018’s “Parabellum,” “Chapter 4” sees our titular gun-fu master recovering after being “rescued” by the charismatic and street-smart Winston (Ian McShane), one of his comrades and manager of the iconic New York Continental hotel (a safe harbor for assassins, so long as they stay in line): that is, being shot in his bullet-proof suit by Winston, falling off a building, and tumbling to the ground with only an awning to lessen the impact. That’s life in the Wick universe, and believe me, there’s plenty more falls to be taken this go around.

With the help of The Bowery King (Laurence Fishburne, relishing his over-the-top dialogue), an underground crime boss and ally, John sets his sights on the all-powerful “High Table” — an international network of contract killers and pompous overlords dressing up savagery in finely tailored suits. They’re governed by strict rules based around golden coins, blood oaths, and age-old traditions — ignored by traditional authorities and the general populace, possessing connections so deep that anyone could be a contract killer. Indeed, this “impossible task” is John’s most challenging yet.

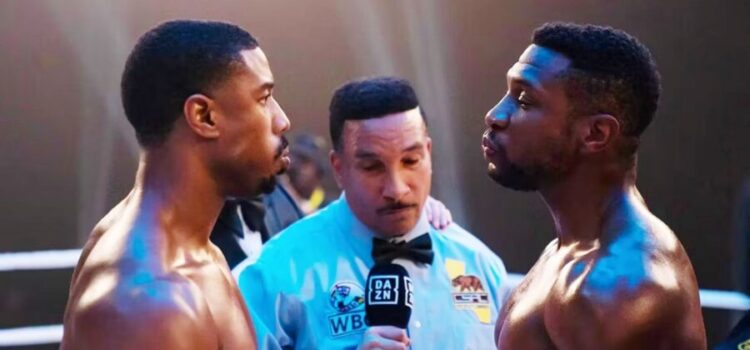

After John executes a key figure of the High Table, they enlist the help of the Marquis Vincent de Gramont (Bill Skarsgård) — a ruthless, egotistical yet insecure enforcer with a questionable French accent. He brings Caine (Donnie Yen), a blind assassin and former friend of John, reluctantly out of retirement to kill the titular ass-kicker once and for all, or else risk his daughter’s death. A haughty tracker named Mr. Nobody (Shamier Anderson), accompanied by a trusty German Shepherd, is also on the prowl, waiting until the bounty on John’s head is high enough, creating further wrinkles for John and the Marquis to iron out. Osaka Continental manager and master swordsman Shimazu Koji (Hiroyuki Sanada), his equally capable daughter Akira (Rina Sawayama), and the aptly named Killa (Scott Adkins), a darkly funny crime boss with golden front teeth, join the party in limited but memorable appearances — as does Lance Reddick as the concierge Charon, whose presence is felt deeply throughout. Reddick passed away earlier this month.

“Chapter 4” zeroes in on the fact that John leaves a path of destruction in his wake wherever he goes, as he begins to question whether the killing will ever cease, and if he’s doomed to forever exist in its shadow. His last-ditch push for liberation has progressed beyond mere revenge for a slain canine, becoming an all-out fight against his seemingly inescapable past — a battle that, in spite of his perseverance, stubborn unwillingness to give in, and sheer force of will, destroys more than it saves.

Notwithstanding this decidedly darker tone than previous installments, however, it’s also just a hell of a lot of fun — nearly three hours of practically unbelievable stunt work, heavily stylized worldbuilding, and cinematic bliss. Some story quibbles aside, every element comes together to solidify “Chapter 4” as not only the best of the series, but one of the genre’s greatest in recent memory.

And oh, what marvelous carnage it is. Even more so than previous “Wick” films, Stahelski consistently ups the ante from sequence to sequence — expertly pacing the mayhem so as to not overwhelm viewers and presenting new variables for John to navigate. As John shoots, stabs, kicks, punches, slices, runs over, and nun-chucks his geared-up opponents, Dan Lausten’s smooth, energetic cinematography follows the performers with precision, unafraid to creatively shake things up to jaw-dropping effect. Traveling to such locales as Osaka, Berlin, and Paris (the setting for a three-act, against-the-clock extravaganza of top-shelf badassery and mythic symbolism), “Chapter 4” never overstays its welcome.

Scenes are bathed in vivid, neon hues: enhancing the lavish backdrops with evocative lighting that dances throughout each frame to complement combat so thrilling, and often laugh-out-loud funny (Caine has some hilarious tricks up his sleeve), that it’s an art form itself. Add to that a head-banging soundtrack from Tyler Bates and Joel J. Richard blending familiar themes with violently rhythmic bass, along with pitch-perfect needle drops, and “Chapter 4” is a stylistic treat.

Despite the extended runtime, “Chapter 4” gives viewers space to breathe, occasionally pumping the brakes to establish more pathos than other films in the series. The first hour or so, for example, largely turns the camera away from John himself — focusing on how the fallout from his vengeful actions have consequences for his friends and those unfortunate enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Caine, too, is facing a moral crossroads — brought back into the fold to protect the person he cares about most, mirroring the struggle John faced with his deceased wife, Helen, brought authentically to life by Yen’s multifaceted performance. All of this combines to make “Chapter 4” a much more melancholic watch than expected — packing all the cheer-worthy mayhem viewers want and expect, while giving everything more weight, and, crucially, tangible stakes.

Reeves continues to dominate the role, though speaking less than in previous entries (which says a lot). It’s clear the acrobatics aren’t so easy for the aging actor to pull off anymore, but in a sense, this lends each punch thrown and received additional impact. Previous films have shown John getting beat up and persisting to come out on top, and “Chapter 4” is no exception — we see his increasing frustration and self-destructiveness as he determinedly demolishes his adversaries, perpetually gearing up for the next onslaught. There’s still plenty of cheesiness in his interactions, thankfully, which brings levity to even the plot’s grimmest stretches.

Alas, “Chapter 4” has some drawbacks. Shay Hatten and Michael Finch’s screenplay crackles with dark humor and is tastefully self-referential, not overloading on quips like a Marvel production. But a bit more subtlety could have benefited “Chapter 4,” particularly in how a certain big twist is telegraphed early on, and is repetitively force-fed to us until the end. An after-credits scene is similarly unnecessary, lessening the impact of narrative decisions made earlier.

This is still an incredible watch — essential for admirers of masterful filmmaking. Amid all the bone-crushing ultraviolence, “Chapter 4” has heart and soul, giving this iconic character another action spectacular for the ages.

John Wick: Chapter 4 is a 2023 action film directed by Chad Stahelski and starring Keanu Reeves, Donnie Yen, Bill Skarsgård, Laurence Fishburne, Ian McShane, Lance Reddick, Shamier Anderson, Hiroyuki Sanada, Rina Sawayama, and Scott Adkins. It is rated R for pervasive strong violence and some language. The runtime is 2 hours, 49 minutes. It opened in theaters March 24. Alex’s Grade: A-

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.