By Lynn Venhaus

Zeitgiest, meet “Urinetown.”

In this Twilight Zone reality we seem to live in now in the 21st century, the subversive “Urinetown” the musical has never seemed timelier. Or funnier. Or scarier.

What once was merely laugh-out-loud outrageous 20 years ago has morphed into a gasp-filled hit-nail-on-head satire where sleazebag politicians are even slimier, greedy corporate bastards are more cruel, ecological disaster seems more imminent and cries of revolution are not far-fetched but absolutely necessary.

This wicked musical comedy composed by Fairview Heights, Ill., native Mark Hollmann, with co-lyricist and book writer Greg Kotis, appears to grow more relevant as the gap continues to widen between the haves and have nots.

Resurrecting one of its past triumphs, from 2007, for the cross-your-fingers 30th season, New Line Theatre’s savvy choice allows a confident, polished ensemble to have fun romping through the ripe-for-parody American legal system, ridiculous bureaucracy, corrupt municipal politics, and foolish mismanagement of natural resources.

The time is 2027 and the focus is urination. Yes, that indispensable body function. But, because we’re in a near dystopian future, there is no such thing as a free pee – and we can’t squander flushes and there is a limited water supply.

If you gotta go, it will cost you. A severe 20-year drought has resulted in the government banning private toilets. Citizens must use public amenities that are regulated by a single evil company that profits from charging a fee to conduct one of humanity’s basic needs.

So, what happens if you disobey? You are punished by a trip to Urinetown, never to return. Egads!

A rabble-rouser emerges – Bobby Strong, and he launches a People’s Revolution for the right to pee. Let’s hear it for urinary freedom! As he does with every role, energetic Kevin Corpuz is passionate in his hero’s journey.

This cast has the vocal chops to entertain in lively fashion, and with nimble comic timing, hits the sweet spot between exaggerated naivete and cheeky irreverence. Jennelle Gilreath, effectively using a Betty Boop-Shirley Temple voice, is the child-like street urchin Little Sally.

Bobby leads the poor rebels – performed by local live wires Grace Langford as pregnant Little Becky Two Shoes, Ian McCreary as Tiny Tom, Chris Moore ss Billy Boy Bill, Christopher Strawhun as Robbie the Stockfish and Jessica Winningham as Soupy Sue.

They are part of a first-rate ensemble in such crisply staged musical numbers as “It’s a Privilege to Pee,” “Snuff That Girl,” “Run Freedom Run,” and “We’re Not Sorry.”

Not only do Hollmann and Kotis take on capitalism, social injustice and climate crisis, but also cleverly twist the great American musical art form itself, with resemblance to Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s “The Threepenny Opera” and the populist champ “Les Miserables.”

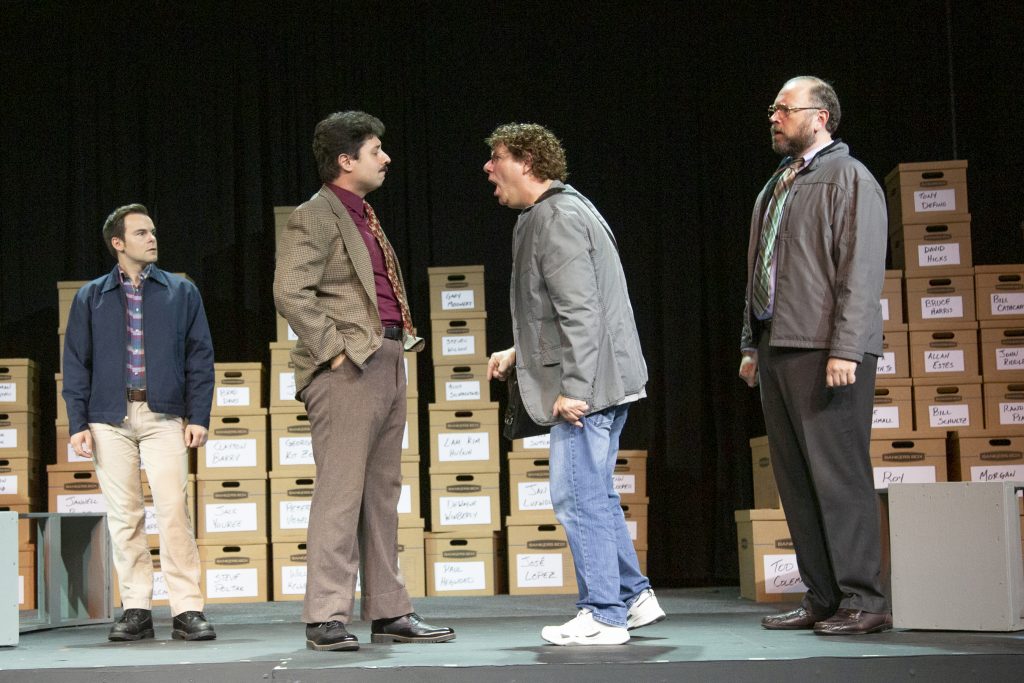

With silly characters modeled after old-timely melodramas, Kent Coffel is Officer Lockstock, Marshall Jennings is Officer Barrel, and Sarah Gene Dowling is tough urinal warden Penelope Pennywise, all having fun with their goofy over-the-top roles.

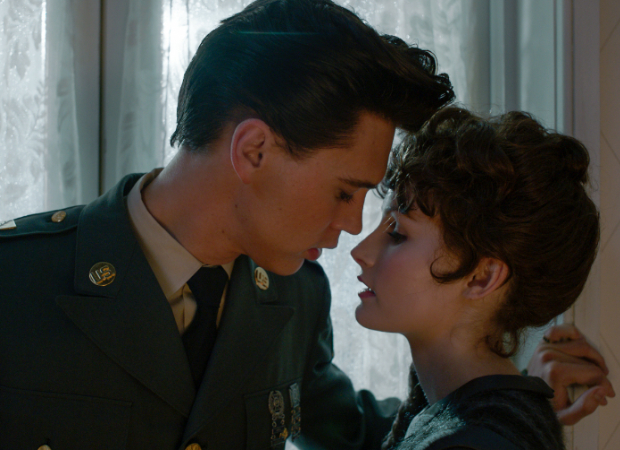

Bobby’s downtrodden parents, Joseph and Josephine Strong, are played by solid veterans Mara Bollini and Zachary Allen Farmer, also doubling as rebels, while fellow New Line regulars Todd Schaefer is the dastardly profiteer Caldwell P. Cladwell and Melissa Felps his darling daughter, Hope, who falls in love with Bobby. Both Schaefer and Felps play it straight, although they are winking to the audience the whole time as the heads of Urine Good Company, aka UGC.

Corpuz and Felps soar in “Follow Your Heart” while Bobby’s “Look to the Sky” and Hope’s finale “I See a River” showcase their skills.

Playing a caricature of an oily grifter and elected official Senator Fipp is Colin Dowd, doing his best Matt Gaetz impersonation, and Clayton Humburg is weaselly as Cladwell’s assistant Mr. McQueen. The “Rich” folk have fun with “Don’t Be the Bunny,”

Co-directors Scott Miller and Chris Kernan’s fresh take goes darker, which suits the capricious winds of an ever-evolving global pandemic that we have lived through for 27 months. Not to mention clinging to a democracy with fascist and authoritarian threats very much present. And hello, global warming.

Kernan’s choreography is a highlight, and music director Tim Clark keeps the tempo brisk. He conducts a tight band of Kelly Austermann on reeds, Tom Hanson on trombone, Clancy Newell on percussion and John Gerdes on bass while he plays keyboard.

The upside-down world we’re in is enhanced by Todd Schaefer’s grimy set, Sarah Porter’s astute costume design, Ryan Day’s sound design Kimi Short’s props, and Kenneth Zinkl’s lighting design.

After an off-Broadway run, “Urinetown” opened on Broadway in 2001 and was nominated for nine Tony Awards, winning for best book, best music score and best direction. The fact that it’s stature has grown over the years is a reflection of our current time – and while that is rather frightening, this show continues to say something worth saying through its devilish use of heightened reality.

It’s holding up a mirror, even though it’s presented in a funhouse way, and that is indeed admirable.

In that spirit, leave your paranoia behind and get ready to laugh at the zingers launched with glee. New Line Theatre’s “Urinetown” is worth a sojourn as time keeps on slipping into the future.

New Line Theatre presents “Urinetown” June 2-25, with performances Thursday through Saturday at 8 p.m. at the Marcelle Theatre. For tickets or more information, visit ww.newlinetheatre.com

Photos by Jill Ritter Lindberg